Jack the Ripper represents perhaps the most perplexing mystery in the history of crime.

A Victorian serial killer who killed five prostitutes in the Whitechapel area of London in 1888, the Ripper’s identity is as elusive today as it was that bloodsoaked Autumn long ago.

Hundreds of books, films and documentaries have speculated on the killer’s true identity, offering countless theories.

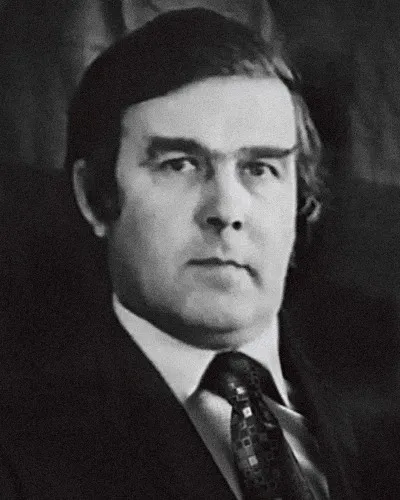

Of all these theories, arguably the most influential and famous was first posited by author Stephen Knight in the 1970s. Knight spun an elaborate tale of conspiracy at the very top of British society — the Royal Family.

He claimed the Ripper’s victims were really killed to cover up a scandalous secret marriage between the Queen’s son Prince Albert Victor, then second in line to the throne, and a Catholic prostitute named Annie Elizabeth Crook, who bore Albert’s child.

Knight got much of his information from Joseph Gorman-Sickert, who claimed to be the illegitimate son of painter Walter Sickert, himself a Ripper suspect. Gorman recounted the story to Knight as told to him by his father.

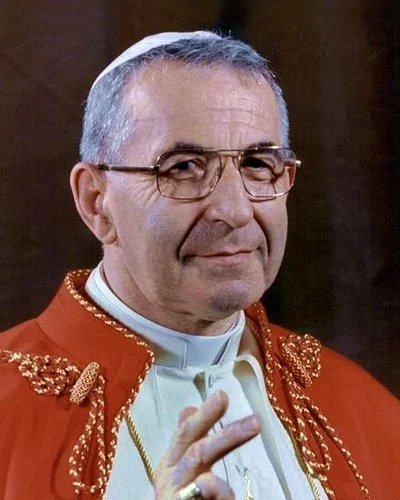

Sir William Gull — a noted physician and purported high-ranking mason, actually committed the murders with the help of accomplices, in order to eliminate everyone who knew of Prince Albert’s secret marriage.

Despite many of the known facts contradicting the story, this royal conspiracy proved immensely popular, inspiring many other authors and numerous films and books.

‘From Hell’, a best-selling graphic novel by Alan Moore used the Royal Conspiracy as a starting point to weave a wider and deeper tale of madness and esoterica and films starring Christopher Plummer, Michael Caine and Johnny Depp also centered on Knight’s thesis.

Were Jack the Ripper’s victims really killed to cover up Prince Albert’s secret marriage?

Evidence for

Real historical figures

Some parts of Knight’s theory seem to be based on verifiable history. Annie Crook was a real person, and she did have a child who was Joseph Gorman’s mother.

However, there is little evidence Gorman’s father was Walter Sickert, beyond his own claims. And Annie Crook didn’t work at a tobacconist as Gorman claimed but was a confectioner’s assistant.

The Juwes

Knight weaves freemasonry into his theory, partially based on supposed ritual aspects to the murders, but also on the famous Goulston Street graffito.

This was a small piece of chalk writing found in an alleyway next to a piece of the bloodied apron of victim Catherine Eddowes. It read — ‘The Juwes are the men who will not be blamed for nothing’.

Knight theorized this was a reference to freemasonry and the murder of Mason Hirem Abiff in Soloman’s Temple by three initiates Jubela, Jubelo, and Jubelum.

Whether this graffiti was related to the murders at all is still hotly contested amongst Ripperologists, and the lack of photographic evidence means the exact spelling of 'Juwes' - crucial to Knight's thesis, remains uncertain.

Evidence against

Gull’s age

At the time of the murder’s Gull was 72, and the previous year he had suffered a stroke that had left him partially paralysed. He had recovered, but his frailty makes him a very unlikely serial murderer — especially one as ferocious and violent as Jack the Ripper.

Gorman recants

After Knight’s book became an international sensation, Gorman — a man who shunned publicity, claimed he had made the whole thing up, possibly in an attempt to take the spotlight off him.

Whatever his reasons, Gorman’s retraction of his story fatally undermines Knight’s theory, which relied almost entirely on Gorman’s account.

The dates

Prince Albert was in Germany for 3 months during the summer of 1884, when, if the birth certificate is correct, Annie Crook’s child was conceived.

If Albert could not have fathered the child, then another central tenet of Knight’s theory collapses.

Victorian gossip

Although the theory was popularised in the 1970s, gossip that the Ripper was a member of high society was popular at the time of the crimes.

The idea that the Ripper was some slumming member of the upper classes was particularly prevalent amongst the emergent tabloid press of 1888 and exaggerated stories of the Ripper’s murders sold many papers.

Rather than passing on some genuine first-hand knowledge of the crimes, Sickert may have just been recounting hearsay and stories that were going around at the time of the murders.

Lack of evidence

Ultimately the theory lacks real, verifiable documentary evidence to back it up. It is almost entirely based on hearsay, rumour and speculation — much of which can be shown to be false.

Knight’s theory is a seductive one, and its sensational nature perhaps makes people want to believe it is the truth behind this most famous of unsolved crimes. But it fails on its most crucial points and remains little more, in the end, than a good story.

Were Jack the Ripper’s victims killed to cover up a Royal scandal? - add your comment below