On Wednesday April 12th, 1961, the Soviet Union announced that cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had become the first man to journey into outer space.

Overnight, the 27-year-old became a national hero and the most famous man in the world, his achievement recognized in front page headlines from Washington to Beijing.

For the Soviets, this was a spectacular validation of the communist system. They had beaten the capitalist Americans to yet another crucial space milestone and demonstrated their technological supremacy to the world.

Gagarin was the perfect face of the USSR. A committed communist, he was also young and photogenic. For Russian leader Kruschev, this major propaganda coup could hardly have gone better.

But not everyone was convinced. Right from the first announcement, there were question marks about the story the Soviet press agencies were putting out.

Several days previously, Western correspondents in Moscow had been tipped off that a successful flight had already taken place. Soviet state TV cameras had even moved in to film them reporting the news.

But the news never came, not until Gagarin’s flight was announced on the 12th. The notoriously secretive Soviets seemed to be spinning the story.

Then the Daily Worker, a British communist newspaper with connections in the Kremlin, reported on the 12th that the launch had actually occurred the previous Friday.

The newspaper claimed, according to its sources, that the flight was a success, but the return to Earth had gone wrong and the cosmonaut had landed far off course and was badly injured.

Was this the reason for the cover-up? Unlike their rivals at NASA, the Soviet space program was run on a military basis and operated under intense secrecy.

It also had a history of covering up its mistakes. It seemed unlikely the Soviet leadership would want to invite the eyes of the world on its achievement if it had gone partially wrong.

If this earlier flight had succeeded in putting a man into orbit, then who was he? Numerous press reports at the time intimated it was a famous test pilot called Vladimir Ilyushin.

Unlike the rookie Gagarin, Ilyushin was the USSR’s most experienced and decorated test pilot. His father was also a famous aircraft designer with close ties to the Kremlin.

Ilyushin, rather than Gagarin, was the obvious choice for such a prestigious mission. But what if the mission was not entirely successful?

In a climate of propaganda and secrecy, could the Soviet leadership really countenance such a perceived embarrassment been revealed to the world?

It is therefore not far-fetched to suggest that Illyushin’s conjectured and ill-fated flight was therefore airbrushed out of official Soviet space history.

But could the truth be far darker than mere cold war paranoia?

Just weeks before Gagarin’s supposed first space flight, two Italian brothers based at an experimental listening station in Turin claimed to have picked up something truly chilling.

It was the sound of a cosmonaut suffocating to death as his capsule spiraled off into space. If genuine, the first man in space never even made it back to Earth.

As for Yuri Gagarin, he never flew into space again. After his initial fame faded, his life begun to spiral out of control. He started to drink and his behavior at official functions was often an embarrassment to the party.

Gagarin died in a mysterious jet crash in 1968, itself subject to many conspiracy theories. Was his sad downfall a consequence of living with a terrible lie?

Had a lost cosmonaut beaten him to the crown of the first man in space?

Evidence for

Rule by secrecy

Whilst the Soviet Union trumpeted its achievements in space around the world, it was studious in concealing its mistakes.

From huge disasters to minor indiscretions, the leadership would airbrush anything regarded as embarrassing, figuratively and often literally, out of the historical record.

In October 1960, at least a 150 people were incinerated on a launchpad after an explosion of an R-16 ballistic missile.

The disaster, later named the Nedelin catastrophe after the chief marshal of the artillery who was killed in the accident, was quickly shrouded in a veil of official secrecy.

It wasn’t until 39 years later, in 1989, as communism began to fall, that the truth was finally acknowledged by the Soviet government.

The death of young fighter pilot Valentin Bondarenko in a fire during cosmonaut training in 1961 was also concealed by the USSR until 1986.

At the other end of the scale, Cosmonaut Grigory Grigoryevich Nelyuboff was expelled from the program for brawling, and his image was subsequently airbrushed out of official photographs.

There were also numerous reports of pre-Gagarin cosmonauts perishing in attempted manned space flights.

In 1959, renowned German rocket scientists Hermann Oberth, then working for the US, quoted American intelligence reports detailing a number of failed manned space launches.

According to the reports, at least 1 cosmonaut died in 1957 or 58, and possibly others in 1959. This coincided with intelligence coming out of Czelovakia which told a similar story.

According to the Czech leak, 4 cosmonauts perished in doomed launches — Aleksei Ledovsky, Andrei Mitkov, Sergei Shiborin and Maria Gromova.

The possibility that these unfortunate men and women may still be floating in the cold of deep space, their capsules having become their tombs, is a deeply disturbing one.

But some extraordinary evidence that emerged from Italy appeared to support this unsettling prospect.

The Italian connection

In the late 1950s, two Italian brothers, Achille and Giovanni Judica-Cordiglia became fascinated by the early space endeavors of the Soviets and Americans.

The pair, keen amateur radio buffs, were excited about the prospect of trying to capture and record transmissions from these early missions.

Using borrowed and scavenged equipment, they set up a listening station in an old WW2 bunker on the outskirts of Turin that they dubbed Torre Bert.

Over the coming years, the station would record thousands of hours of flight telemetry and voice communications from Sputnik, Vostok, Explorer and numerous other Soviet and American programs.

In 1960, the brothers made headlines in Italy and around the world with their claim that they had heard communications from secret, clandestine Russian space launches.

What made this so sensational was, according to the brothers, the cosmonauts involved had died in space.

In May 1960, they first picked up communications from what appeared to be an unpublicised manned Soviet flight. If so, presumably it had failed to return its occupants to Earth alive.

Interesting corroboration for this came from writer Robert A. Heinlein, who heard of such a manned attempt from Russian soldiers whilst traveling in Vilnius in May 1960.

Later that year, Torre Bert tracked a faint SOS signal from a craft that seemed to be departing Earth’s orbit. Again, if this recording was genuine, we would have to assume the men had not survived.

Then, just weeks before Gagarin’s putative flight, the brothers claimed to have captured the forced breathing and rapid heartbeat of a dying cosmonaut as his spacecraft faltered in Earth’s orbit.

Were these lost cosmonauts, like those mentioned in the earlier American and Czech intelligence reports?

The station in Turin continued to pick up broadcasts of apparently doomed Soviet missions for the next few years, including the desperate last words of a female cosmonaut before she burnt up on re-entry.

In 2001, a senior engineer on the Soviet space program came forward to confirm what the brothers had seemingly caught on tape.

Mikhail Rudenko told Pravda that spacecraft with pilots named Ledovskikh, Shaborin and Mitkov were launched from the Kapustin Yar cosmodrome in 1957, 1958 and 1959.

“All three pilots died during the flights, and their names were never officially published,” Rudenko said.

But not everything the listening station picked up was so horrific. One transmission seemed to suggest someone else had made it into space and back just days before Gagarin’s official flight.

Vladimir Ilyushin

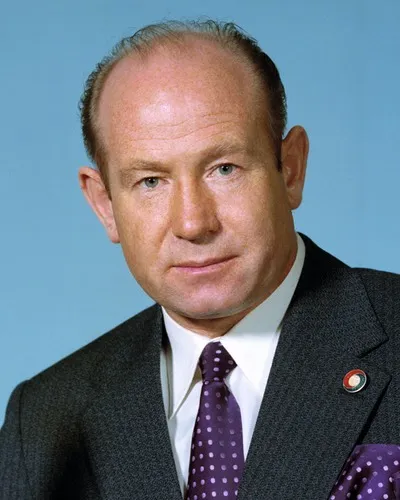

Vladimir Sergeyevich Ilyushin was Russia’s greatest test pilot and holder of multiple speed and altitude records.

For those skeptical of Yuri Gagarin’s claim to be the first man to travel into space, Ilyushin is the most likely alternative. Or, at least, the most likely alternative that made it back to Earth alive.

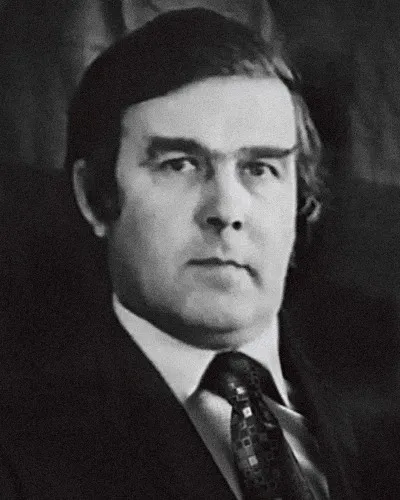

Ilyushin was named as the ‘true’ first man in space by foreign journalists in Moscow in the days surrounding Gagarin’s purported historical flight.

Denis Ogden of the British Daily Worker and French journalist Eduard Bobrovsky were amongst the first to identify Ilyushin and many others soon followed, supposedly on the basis of inside information.

Ilyushin had the perfect credentials for the part. He was the son of a legendary aircraft designer — Sergei Ilyushin and a decorated test pilot in his own right. The family also had impeccable links to the Soviet establishment.

His whereabout around the time of Yuri Gagarin’s flight were shrouded in mystery. In all the fanfare and pomp surrounded the Gagarin triumph, Ilyushin — one of the countries great heroes, was nowhere to be scene.

The official story had it that his absence was because he had had a car crash the previous month and was recovering in hospital. However, this was only the first of many stories.

Throughout the aftermath of the Gagarin flight, the Soviet state press agencies, so adept at propaganda, seemed unable to give a consistent account about Ilyushin.In reaction to the foreign press stories that he had been the true first man in space, the Soviets simply denied he was even a cosmonaut.

However, in the month’s before Gagarin’s flight, news that Ilyushin was in cosmonaut training had already made it to the Soviet press. There was even a photograph of him in a space suit published in the newspapers.

The details of Ilyushin’s supposed crash also changed numerous times. Now it was so serious that it had put him in a coma for almost a year, making it impossible for him to have undergone the cosmonaut training at all.

This too was undermined by another photograph that appeared showing him looking decidedly conscious and healthy during this time whilst receiving the Hero of the Soviet Union award.

The reason for his prolonged pubic absence also evolved. The new story had Ilyushin recuperating from his car crash in China, an explanation that raised many eyebrows amongst seasoned foreign correspondents in Moscow.

The Soviet healthcare system in 1961 was extensive and of a high standard. It sounded deeply unlikely that it would send such a prestigious figure to a foreign country for treatment.

Where these unconvincing and shifting accounts simply a cover for the truth the journalists had been reporting all along?

And was the strange story of Ilyushin’s absence designed to hide the embarrassing fact that, whilst he had made it into space and back, he had landed miles off course in mainland China?

Evidence against

The recordings

The famous Judica-Cordiglia recordings represent perhaps the most compelling evidence for the theory that other cosmonauts made it into space before Gagarin.

The brothers became extremely famous in the Italian press because of their recordings and were subject to many national and international newspaper reports.

However, some science writers and space experts who have examined the Italian brother’s evidence have cast doubt on the veracity of their claims.

Several aspects of the brothers recordings did not match known technical and operational details of the Soviet space program, such as the correct communications protocols used by the cosmonauts.

Their recording of a craft leaving Earth’s orbit was obviously suspect as the Soviets had no ability to leave orbit in 1961. They did not achieve this capability until 1969.

The famous tape with an audible heartbeat supposedly from a dying cosmonaut is also unlikely to be genuine, as the Russians did not broadcast such information across audio channels.

But perhaps the biggest problem with the brother’s claims is the fact nobody else was able to reproduce them.

Whilst the set up at Torre Bert was superb for amateurs, it paled in significance compared to the far more sophisticated radio monitoring arrays set up by the Americans, British, French, and Germans.

"We have no reason to believe that there have been any unsuccessful manned space attempts by the USSR"

Bernard Lovell

Yet such powerful installations as Jodrell Bank in the UK and the American’s huge listening station in Turkey had not observed the Russian failures claimed by Torre Bert.

Bernard Lovell, director at Jodrell Bank, wrote in 1963 — “We have no reason to believe that there have been any unsuccessful manned space attempts by the USSR”.

We could surmise that Lovell was lying, but to what purpose? For the West to forgo the immense propaganda value of exposing Russian lies and failures at the height of the cold war seems improbable.

By the early 1960s, the Americans were lagging far behind the USSR in the space race and such an opportunity to exploit the reckless indifference to human life of the Soviets would have surely been taken.

The obvious conclusion is the Judica-Cordiglia brothers had, at best, made a mistake. Some have suggested that their recording of a dying cosmonaut was actually one of the many dogs the Soviets sent up into space.

A less charitable explanation is the brothers had fabricated the communications and the whole thing was a hoax. Some of the events they claimed to have captured tended to support this.

In particular, the recording purporting to be a female Cosmonaut’s last words as she burns up on re-entry contains poor Russian, broken grammar and many gibberish phrases.

Soviet cosmonauts were renowned for been extremely well educated and the idea that they would send someone into space with such a poor command of their own language is unlikely.

In contrast, the Judica-Cordiglia brother’s own sister had begun to learn Russian in order to help them with translations of the tapes. Her level of Russian was much more consistent with the voice on the tapes than a genuine cosmonaut.

Whilst there is no doubt the brothers had made genuine recordings, had they fabricated the more sensational tapes in order to keep themselves in the limelight?

Misplaced confidence

One curious fact seriously undermines the idea that the Soviets had covered up earlier, failed manned space flights.

If they were so intensely paranoid about even minor failures becoming public, would they have alerted the world to Gagarin’s flight whilst he was still in orbit?

The Soviet space authorities actually announced Gagarin’s feat 30 minutes before the landing, and even prepared press releases in case his flight landed off course and they would require international assistance.

Clearly, the Kremlin took a pragmatic view of the prospect that a cosmonaut’s re-entry into Earth may go wrong, especially with the possibility that they may end up in a foreign country.

It therefore makes little sense that they would have gone to such lengths to cover up Ilyushin’s supposed off course landing just 5 days before.

The Ogden story

Some critics have questioned the original source of the story that Vladimir Ilyushin was the real first man in space.

Since 1961, almost every version of the theory has been based on the same April 11th newspaper article in the British communist newspaper the Daily Worker.

Journalist Dennis Ogden was responsible for the story, and always claimed to have based it on a reliable inside source. But since he refused to name it, it was impossible to verify the information.

Many critics think Ogden’s source was really a figleaf to cover the fact he had jumped to a rather embarrassing conclusion.

Ogden was a neighbor of Ilyushin and had noted his public absence. When, a few days before Gagarin’s flight, he had heard rumors of a launch, he simply had a journalistic hunch it was Ilyushin on board.

The story was little more than a guess on Ogden’s part. A guess that was reported around the world and is still cited as evidence of a cover-up 50 years later.

That Ogden himself had little confidence in his own scoop is obvious. The very next day he wrote a story in the Daily Worker proclaiming Gagarin as the first man in space after all.

Did lost cosmonauts make it into space before Yuri Gagarin? - add your comment below