We'll never know what Somerton man thought the day would have in store for him as he stepped off a train at Adelaide station one Australian summer morning in 1948. All we know is he was heading to his death.

The man's strange demise on the beach at Somerton would spawn Australia's greatest unsolved mystery, a secret code that remains unbroken to this day and persistent rumours of Cold War intrigue and spying.

The story begins on the morning of December the 1st 1948 at a beach near Glenelg, seven miles from the South Australian city of Adelaide. Local jeweller John Lyons had become concerned about a man he had seen the previous evening laying fully clothed on the sand propped up against the sea wall.

Lyons had initially dismissed the slumbering figure as a drunk sleeping off a rough session, but the next morning he was still there. Cold and pale, an extinguished half smoked cigarette resting on his shirt collar, the man was clearly dead.

Lyons alerted the police; If this unfortunate soul was a drunk his hangover had proven terminal. But it seemed unlikely even at first glance, the man was clearly no vagrant as he was well dressed in a suit, pullover and tie and what looked like freshly polished shoes.

What initially might have been something relatively straightforward like illness or suicide quickly became a whole lot more complex and puzzling by the troubling details of the man's death.

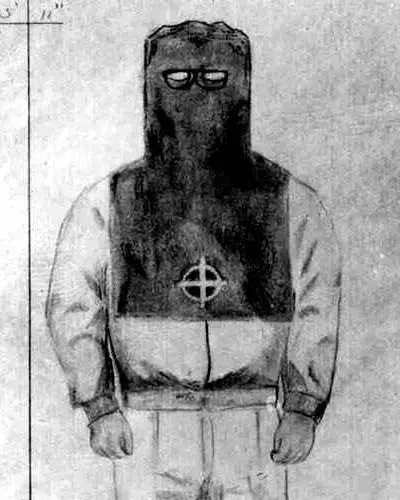

Somerton man, as he became known for reasons about to become clear, was about 45 years old, in excellent physical condition, with unusually well defined and muscular calfs and smooth well-manicured hands.

Found on his person was some Juicy Fruit chewing gum, a couple of combs, a box of Army Club cigarettes with more expensive Kensitas cigarettes inside, a used bus ticket to Glenelg and an unused train ticket to nearby Henley beach.

The trouble for the police was that was it. Aside from this small assortment of items, the body was entirely and utterly anonymous. No wallet, passport or identification documents. Strangest of all, the labels in his clothing had been deliberately removed.

Whoever Somerton man was, he either wanted to remain anonymous or somebody had stripped the body of any form of identification. If the case wasn't already difficult enough for the Adelaide police, no cause of death could be ascertained either.

There were no marks on the body or signs of a struggle and the autopsy revealed he had not died of a heart attack or other natural causes. There was, however, signs of damage to his organs - the brain, stomach and liver were congested with blood leading the pathologist to suspect he had died as the result of hemorrhaging caused by poison.

The pathologists were puzzled. It was the only explanation for his death they could come up with but even this made no sense. Absolutely no traces of poison were found in the man's body and there were no signs of convulsing or vomiting at the scene.

If this was a poisoning then it was a very sophisticated one, using a rare poison that left no trace, odd for small town Australia in the 1940s. It also looked like murder rather than suicide as the body's peaceful and undisturbed state when discovered suggested it had been moved into position after the poison had taken effect.

Whatever the case, it appeared the work of professionals. The stripping of identification from the body, the removal of all the tags from his clothing, the signs of a sophisticated, traceless poison; it all pointed to the world of espionage. Was Somerton man a spy?

A few scant leads emerged. A couple of locals suggested he was a man named E.C. Johnson, but when Johnson promptly walked into Adelaide police station alive and well that possibility evaporated. All other enquiries proved fruitless. Even searches as far afield as the UK and US returned nothing.

Just days after Somerton man's discovery, the case was as cold as the body on the slab. No name, no clues, a dead end. On December 10th the body was embalmed, the first time anyone could remember this happening to an unidentified person.

For the next six weeks, Somerton man was little more than a local curiosity, all enquiries exhausted. Then, on January 14th 1949, a breakthrough was made when staff at Adelaide train station finally made a connection between media reports of the mystery man found at Somerton and an unclaimed suitcase that had been resting in their cloakroom since December.

Inside the suitcase police found clothes similar to those Somerton man had been wearing. The dates checked out too, as it had been deposited at the station the day before the man's body had been found. A distinctive yarn of orange barbour waxed thread inside the suitcase clinched it - the same orange thread had been used to repair the pocket of Somerton man's trousers.

It was his suitcase alright; were police finally about to solve the mystery? Unfortunately, the contents of the suitcase were of little help in identifying Somerton man. If anything, what was inside only deepened the mystery.

It was mostly the kind of mundane stuff you'd expect in a suitcase - a dressing gown, a pair of trousers, a pair of slippers, underpants and pajamas, shaving equipment, pencils, envelopes and stamps. More interesting was a knife and scissors, a square of zinc and a stencilling brush of the kind used by seaman to mark cargo on merchant ships.

Perhaps Somerton man was a foreign sailor? It certainly seemed he was not Australian, or if he was he was a frequent traveller abroad. Both the barber thread and the man's coat were of a kind not sold in Australia.

Ominously, like the clothes the man was wearing, almost everything in the suitcase had had its label deliberately mutilated. There were, however, a couple of notable exceptions. A washbag bore a label with the name 'T. Keane' on it and the name 'Kean' was found on a singlet.

Whilst this was an important clue, investigating detectives Lionel Leane and Len Brown were confused. Why had all the other labels been so meticulously removed yet these left intact? They felt the distinct possibility that somebody was deliberately trying to mislead them.

Regardless, a search for T Keane and Kean in missing persons records in the whole English speaking world returned nothing. One possibility was the man was from the Eastern Bloc, whose records were off limits to Western investigators with the onset of the Cold War.

Again, it looked like the police had reached another dead end. After six months with no further leads, a coroner's inquest into the mystery man's death finally commenced on June 7th 1949. With little new evidence to go on it came to much the same conclusion reached back in December.

Pathologist John Burton Cleland stated, "I would be prepared to find that he died from poison, that the poison was probably a glucoside and that it was not accidentally administered; but I cannot say whether it was administered by the deceased himself or by some other person."

Despite the inconclusive verdict, a major discovery was made at the inquest; initially missed by the pathologists was a small scrap of paper hidden inside the fob watch pocket of Somerton man's trousers. It would change the whole complexion of the case.

It was torn out from a page of a book of poetry called the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and contained the phrase 'Tamám Shud'. The Rubaiyat itself is concerned with the themes of seizing every day and leaving behind no regrets. Tellingly, Tamam Shud means 'ended' or 'finished' in Persian. The implication that Somerton man had used the book as an impetus to suicide is obvious.

Police went to the media with the new finding in the hope that somebody would be able to identify the book the scrap had been torn from. They were soon contacted by a man, who wished to remain anonymous, who had found a rare 1859 Edward FitzGerald translation of the Rubaiyat on the back seat of his unlocked car which had been parked in Glenelg around the time the body was found.

Forensic experts matched the torn scrap to a page from the book, but nobody had any idea why it had been ripped out or indeed why it had been sewn into the man's trousers. None of it made any sense.

It is probably the discovery of the book more than anything else that ensures we're still talking about Somerton man 70 years later. It would turn an obscure John Doe case into one of the most baffling and intriguing mysteries of the entire Cold War. And like many great mysteries, this one had a secret code.

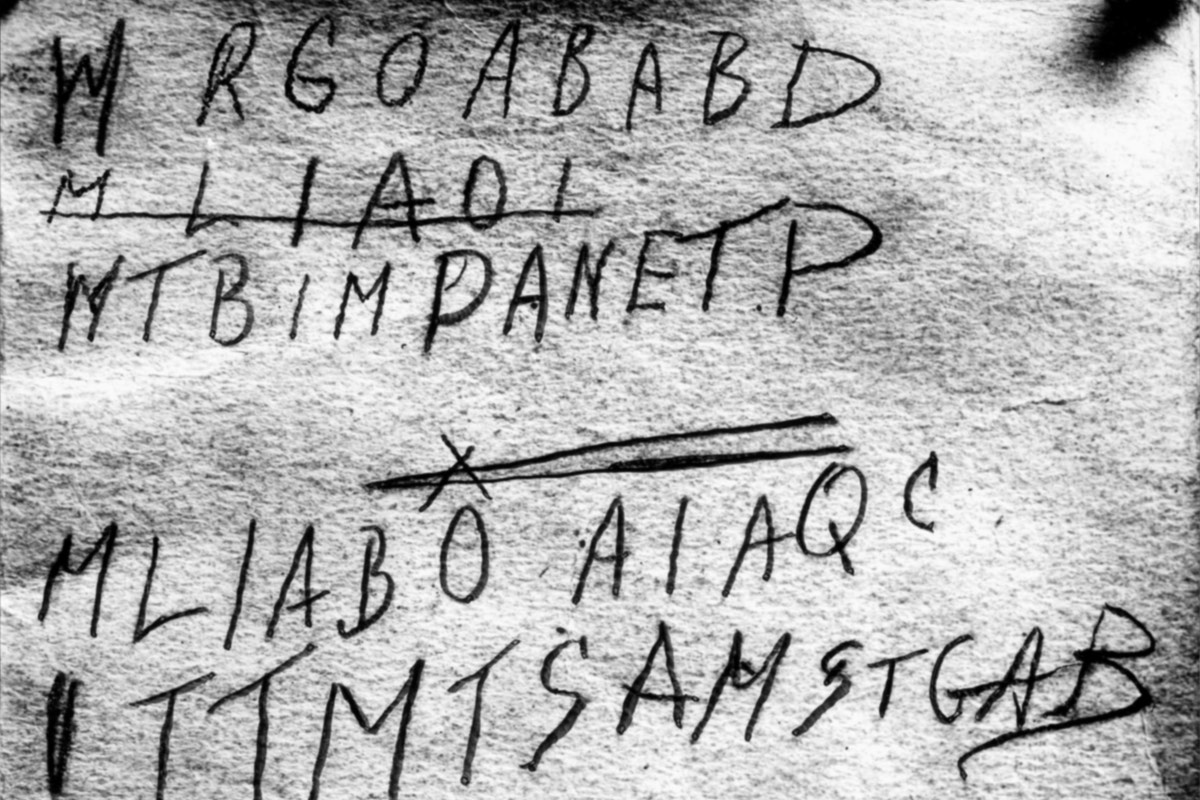

Aside from the torn out scrap, the forensic experts also found very faint letters written in pencil on the book's inside cover. It looked like some kind of code or cipher:

Also written in the book was something less cryptic, an unlisted telephone number that belonged to a local nurse named Jessica Thomson. Thompson lived less than a mile from where Somerton man's body was found and was clearly connected to the dead man in some way.

At the time of the police inquiry, Thompson requested and was granted anonymity by the police, and was referred to for many years only by the name 'Jestyn'.

The detectives who interviewed Thompson noted her evasive manner, seeming reluctant to offer up any information about what, if anything, she knew. Most startling was her reaction when shown a plaster cast of the dead man's face. Thompson was visibly shocked and was described by detectives present as "completely taken aback, to the point of giving the appearance that she was about to faint."

Despite this extraordinary reaction, Jessica Thompson claimed not to recognize Somerton man, but did tell police that she too had once owned a copy of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. Thompson had worked as a nurse in Sydney during WW2 and recalls giving her copy of the book to an army lieutenant she had met there called Alf Boxall. Was this a tale of an old love tracking down his wartime sweetheart in the hope of a reconciliation?

Hoping they might finally be closing in on the solution to the mystery, and the identity of Somerton man, police attempted to track Boxall down. Unfortunately for them but fortunately for Boxall, they found him alive and well and living in Syndey.

Boxall still had his copy of the Rubaiyat, complete with the intact page bearing the phrase Tamam Shud and signed with 'Jestyn', Thompson's pseudonymous name. Boxall claimed no knowledge of the dead man and said he had not had any contact with Thompson after 1945.

Clearly Thompson and Boxall were not been entirely honest. Two copies of a book of poetry, owned by two men, both inscribed with direct references to the same woman. There had to be a connection and some of the detectives' long held suspicions about the case began to become manifest.

The code, the missing labels and the air of mystery surrounding the dead man raised the possibility his death was espionage related, and he himself may even have been a spy. Did Thompson and Boxall know more than they were letting on? Were they both spies themselves, unable to tell police what they knew because it was top secret?

That there might be darker forces at work here was reinforced by the discovery of another similar death in 1945 were a Sydney man named George Marshall also died, supposedly from poisoning, clutching a copy of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. Was the book some kind of standard issue for spies? Was it used for identification or as a book cipher?

Australia in the post-war period was thick with espionage. The UK and US both suspected the Soviets of operating agents in the country, which housed such highly sensitive installations as the top secret British rocket and nuclear test base Woomera, 300 miles north of Somerton.

The spying thesis was clearly credible, and the suspicious silence of those involved only reinforced the idea. But after failing to get anywhere with Boxall, and with Thompson no help, the case eventually went cold. Interest would periodically be revived, with dozens of people over the years coming forward claiming to know who Somerton man was, but on every single occasion the leads amounted to nothing.

Much later, in the 1970s, Alf Boxall would be interviewed on Australian TV. Whilst admitting he had been involved in intelligence during the war, he denied there was any spying connection in the Somerton man case, stating, "It's quite a melodramatic thesis, isn't it?

"It's quite a melodramatic thesis, isn't it?"

Alf Boxall

But Boxall's attempts to downplay the idea have had little effect on its enduring popularity and the case has never been far from the public consciousness in Australia. Rumours that this was an untold and still untellable story of Cold War intrigue persists to this day.

Was the nameless, mystery man found on Somerton beach really a spy, killed in the course of some clandestine mission?

Evidence For

The Spy Game

Several aspects of the Somerton man case are suggestive of spying. Whilst innocent interpretations can perhaps be found for each, when taken as a whole it's difficult to justify an alternative explanation.

As discussed, the lack of documents and the removal and mutilation of the man's clothing labels look like an attempt to obfuscate his identity. However, it seems unlikely Somerton man himself would have done this. If he was a spy or undertaking some kind of criminal activity, it would have been necessary to assume a false identity rather than be entirely anonymous.

Instead, it seems the stripping of Somerton man's identity was done by a third party seeking to ensure the man's death would leave a dead end for investigators. Clearly, there is a strong likelihood whoever did this was also responsible for his death.

In the pre-DNA era and with the absence of any witnesses, an anonymous victim would be almost impossible for the police to identify. This also ensures no motive for the death can be ascertained and no possible likely perpetrators.

The method of the man's death also signals this case out as something more than a regular suicide or murder. The original investigators in 1948 were sure he had been poisoned but were unable to ascertain exactly how and with what substance. The murder had been committed with such skill and with a poison that was sufficiently obscure and untraceable that it singled out the perpetrators as professionals.

A more recent examination of the case in 1994 reasoned the poison was probably digitalis. John Harber Phillips, Chief Justice of Victoria and Chairman of the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, reviewed the case to determine the cause of death and, noting the engorgement of the man's organs, concluded that "There seems little doubt it was digitalis."

However, other experts are skeptical that digitalis was used in this instance. Whilst it is possible to use digitalis as an 'untraceable' poison, this is mainly due to its ability to mimic a heart attack coupled with its widespread use as heart medication. This had led to some murders been overlooked by pathologists as overdoses of legitimate prescriptions.

In actual fact, digitalis is not innately difficult to detect and would have probably been discovered in Somerton man's case as his death was suspicious and unexplained. If he was poisoned it was, therefore, more likely to be something more obscure and esoteric that would not be detected without prior knowledge of its use.

Since the 1920s, the KGB had been experimenting with producing exactly such poisons. The infamous Laboratory No 12 was originally set up by Lenin in 1921 and expanded its remit under Stalin in the 1940s. It was specifically tasked with producing unique and untraceable substances, often by combining known poisons in unusual ways with the specific intention of mimicking natural causes and baffling forensic investigators. Undoubtedly, the western agencies had similar departments.

Was Somerton man killed by one of these exotic poisons? Perhaps the mystery man was a double agent whose treachery had been discovered by the Soviets or even a Soviet agent whose operation in Australia was discovered by Western intelligence. Even the suggestion a country had been penetrated by foreign intelligence could do so much damage that it would routinely be covered up, providing a satisfactory explanation as to why Somerton man had been stripped of all identification.

It is perhaps the book and cipher that is most redolent of spying, evoking as it does countless fictional tales of espionage. The five line, 50 character message has prompted endless debate over the years, with many amateur code breakers and even department of defence cryptologists attempting to discern its meaning. So far all have failed and it's true purpose and intent remain unknown to this day.

Some have speculated it is not a cipher at all, but some kind of mnemonic or acrostic. If the message is in English, then linguistic analysis of the text conducted by Professor Derek Abbott at Adelaide University reveal its more likely that the letter frequencies of the message correspond to the first letters of English words rather than normal English text.

Others believe the text is merely gibberish, the fevered product of a disturbed mind. Whatever the case, its placement in a book of poetry is almost more interesting. The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam is clearly significant as it appears three times in this story. Was it being used as a book cipher?

When the Australian Navy cryptographic department examined the letters, they came to just that conclusion, "a reasonable explanation would be that the lines are the initial letters of words of a verse of poetry or such like."

A book cipher has been a common spy technique as long as books have existed. The essential principle is that the key to the code in question is a section of text in a book or other commonly available published material. If a book is used, it is usually required that both sides of the communication use the same edition.

In the American Revolution, Benedict Arnold used such a book cipher, known as the Arnold Cipher, with Sir William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England acting as the key.

Had the Rubaiyat of Omar Kayam been used as the key in some spy ring operating in Australia? The book crops up no less than three times - the copy linked to the dead man by the scrap of paper bearing the phrase Tamam Shud, the copy Jessica Thompson says she gave to Alf Boxall, and the copy found clutched to the dead body of George Marshall in Sydney in 1945.

Whilst this collection of 11th-century Persian poetry is a common one, the editions in this case were far from ordinary. The Somerton man edition was an extremely rare 1859 translation by Edward Fitzgerald. So rare in fact, that when author and former policeman Gerry Feltus led an exhaustive global search for other copies the closest he was able to get was a similar Whitcombe & Tombs version that was published in a squarer format.

The George Marshall version was even stranger, not so much rare as apparently none existent. His copy claimed to be a seventh edition published in London by Methuen, but records reveal no such edition was ever produced, the Methuen run ending at the fifth.

George Marshall's curious death also provides a link to the third copy of the book. Marshall died of an apparent suicide by poisoning in Sydney in 1945, close to where Jessica Thompson and Alfred Boxall were working at the time and the same year Thompson gave her copy of the Rubaiyat to Boxall.

It looks far more than coincidence that the book crops up so often and that the editions involved are so peculiar and suspicious. Could it be they were actually not genuine copies of the book at all but espionage paraphernalia designed to be used as book-ciphers or one-time pads?

A one-time pad is an additional, entirely random one-off key that makes a cipher essentially uncrackable. They were often employed in the Cold War by Soviet spies operating in America to secretly communicate with their Russian embassies and consulates. There is not a single instance of any of the American intelligence agencies managing to crack such a code.

Jessica Thompson and Alf Boxall's role in the story of Somerton man have also caused many to suspect their involvement in espionage. Boxall admitted in the 1970s he was involved in intelligence during the war and in recent years, Thompson's daughter Kate has stated she now believes her mother was a Russian spy.

"There's always that fear that I've thought that maybe she was responsible for his death."

"She had a dark side, a very strong dark side," Kate told Australian current affairs show 60 Minutes. "She said to me she, she knew who he was but she wasn't going to let that out of the bag so to speak. There's always that fear that I've thought that maybe she was responsible for his death."

Kate Thompson also revealed how her mother spoke Russian and would hint that the Somerton man mystery was "above state police level". If Kate Thompson's suspicion about her mother are correct they have particularly dark implications considering both Somerton Man and George Marshall died in strange circumstances within a mile of where Jessica Thompson was living at the time.

There are many examples of Russian sleeper agents living normal lives in the West for years and decades entirely unsuspected by those around them. The Portland spy ring in the UK in the 1950s involved several Soviet agents conducting normal lives as British citizens and American couple Richard and Cynthia Murphy lived in suburban New Jersey for 15 years before been exposed as Russian spies Lydia and Vladimir Guryev in 2010.

Was Jessica Thompson such a sleeper agent, operating silently in Australia for decades?

The Hot Cold War

Although far from the Western theatre of the Cold War, Australia was a hotbed of espionage activity in the post-war period, with it playing a key strategic role for both the US and the UK in the period following WW2.

Both countries were concerned about the security of intelligence in the country. Shortly after the war, the joint US-UK counterintelligence programme Venona discovered a leak operating out of Canberra which was passing sensitive government secrets back to the Soviets.

Because of this and other incidents, a dedicated Australian intelligence organisation was formed - the ASIO, closely modelled on the FBI and Britain's MI5. The latter agency was especially influential, providing much of the initial personnel and expertise on ASIO's formation.

It was around the time of Somerton man's death that the MI5 team was in Australia to consult over the creation of the ASIO, and the new agency operated an office out of Adelaide close to where the body was found. Was there a connection?

Some of the MI5 delegation such as Roger Hollis and Robert Hemblys-Scales were suspected of been Soviet agents themselves, and the ASIO would later have its own problems with Soviet moles. The ACP - Australian Communist Party, was also viewed with suspicion by the Americans due to its susceptibility to Russian infiltration.

The ASIO orchestrated defection of Soviet diplomat Vladimir Petrov in 1954 also provided a great deal of new intelligence about Russian spying in both the United States and Australia, including the long suspected spy ring operating from the ACP.

With the country playing such an important strategic role for the Western powers, initially as the home of the UK's top secret nuclear and rocket testing base at Woomera, then as a key part of the Cold War Five Eyes surveillance programme, it's inevitable there were active intelligence networks been run by both sides in the country.

Whether Somerton man, Jessica Thompson and Alf Boxall were some small cog in those operations we may never know. Whilst much of the evidence is circumstantial and suggestive, there are enough fingerprints of espionage in their story to suspect they were.

Evidence Against

Affairs of the heart

An alternative way to look at the strange case of Somerton man is not as a story from the pages of spy fiction but one from the pages of romance. At least some of the evidence can be fit into a scenario of unrequited love, a WW2 dalliance that ended in tragedy on Somerton beach three years later.

There is some reason to believe somebody was looking for Jessica Thompson the day before Somerton man died. A witness who came forward several years later recalled a man knocking on her door the day before Somerton man was found.

Since we know Jessica Thompson was in the habit of giving copies of the Rubaiyat to men she knew, and Somerton Man's copy contained her unlisted telephone number, it's safe to assume the two were acquainted. It's possible the man was a foreign sailor judging by the stencilling brush found in his suitcase, an item used to stencil cargo on merchant ships.

At some point in the previous few years the pair may have and had a romantic liaison. For some reason they were parted and Thompson gave Somerton man a copy of the Rubaiyat as a keepsake of their time together.

An intriguing additional possibility is that Somerton man fathered Thompson's young son Robin, who was 18 months old in 1948. Several investigators have pointed to a couple of unusual features of the man's ears, an enlarged upper cymba and a diagonal ear crease, clearly present in the morgue photos and drawings of his corpse. These features are present in only around 1% of the population and are also evident in Robin. Was Somerton man his father?

The main issue with this scenario is how and why Somerton man ended up dead. Although the pasty found in his stomach was dismissed at the time as the cause of the man's death, Nick Pelling on his blog ciphermysteries.com suggests the excessive sulphites used as preservatives in baked goods in 1948 may have caused an extreme allergic reaction.

This might initially seem far-fetched, but it was clear from the autopsy that Somerton man was probably recovering from a serious illness when he died. His enlarged spleen is unlikely to have suddenly occurred on the day and is more suggestive of him having recently suffered from something like mononucleosis or malaria.

Pelling theorises that in his already frail state our man became ill after consuming the pasty at Jessica Thompson's house, lay down to try and sleep it off and died. This scenario fits the autopsy evidence which noted the lividity at the back of the man's neck, something unlikely to have occurred if he died whilst sat propped against the seawall where he was found.

It's possible Thompson then persuaded a male friend to move the body onto the beach to make it look like he died there, presumably to save the embarrassment and difficulty of having to explain how a strange man was found dead in her house. A witness who came forward much later in the 1950s did indeed claim to see a man on the beach carrying another man over his shoulder at some point on the evening before Somerton man was found dead, so there is some corroborating evidence for the idea.

Whilst clearly speculation, the general scenario has some merit and cannot be discounted. The main objections are the lack of credible explanations for the book and code, and the inability to ever identify the dead man. If this was simply an innocuous domestic incident then why has Somerton man resisted identification for nearly 70 years?

HC Reynolds

In recent years, a new theory has emerged as to the identity of Somerton man. In 2011, a woman approached Adelaide based biological anthropologist Professor Maciej Henneberg with an old military service card that had belonged to her father. The US seaman's ID card featured the picture of an 18-year-old British man named H.C. Reynolds.

According to Henneberg, the man pictured on the card is probably the same man found on the beach at Somerton. "It's not just about an exact image...there is a close similarity of the ear, and ears don't change."

"It's not just about an exact image...there is a close similarity of the ear, and ears don't change."

Henneberg noted several other similarities in the nose and lips, but was particularly convinced by a mole on the man's cheek. "Such moles change little with age, though size may slightly differ," he said. "Together with the similarity of ear characteristics, this mole, in a forensic case, would allow me to make a rare statement positively identifying Somerton man as H. C. Reynolds."

Whilst this may look convincing on the surface, there are problems. As with several other witnesses in the case, H.C. Reynolds' daughter has requested to remain anonymous and her claims have proven difficult to verify. Searches conducted by the US National Archives, the UK National Archives and the Australian War Memorial Research Centre have failed to find any records relating to H.C. Reynolds.

Other researchers have found possible civilian candidates named H.C. Reynolds, but the closest match died in 1953, not 1948.

Like so many leads in this case, this could prove to be yet another dead end, leaving us no closer to the solution to the mystery. All we really know is a man died; alone on a beach, unknown, unclaimed, perhaps unloved.

Maybe the most fitting epitaph to this story comes from the book at the center of the mystery, the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam:

Was the unidentified man found dead on an Adelaide beach in 1948 a Cold War spy? - add your comment below