The American author Henry James once said, "I am haunted by the conviction that the divine William is the biggest and most successful fraud ever practiced on a patient world."

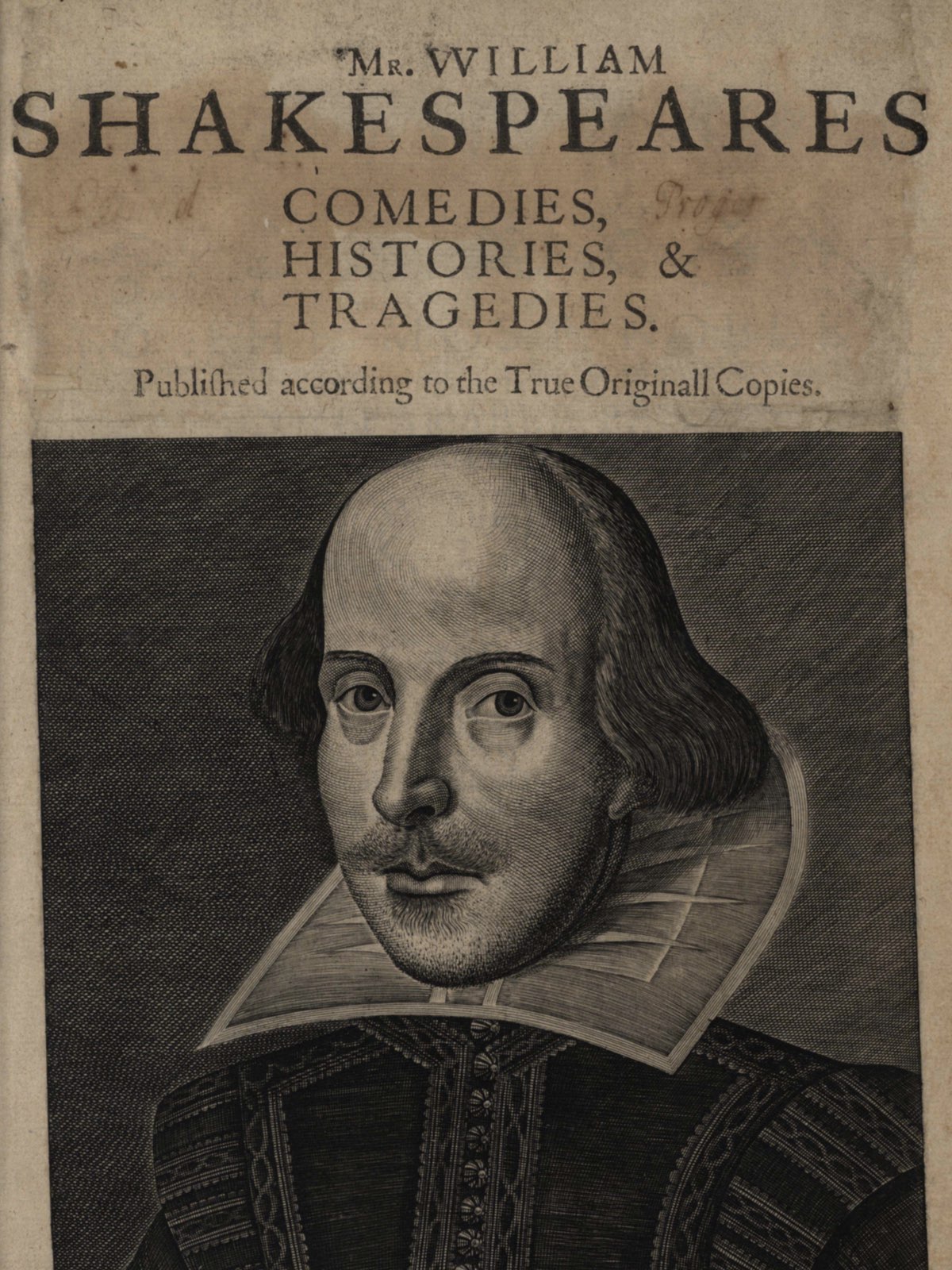

The William that Henry James is referring to is William Shakespeare, widely regarded the English language's greatest ever writer. Shakespeare's influence on our collective culture is incalculable; his characters, his stories and most of all his words are part of the fabric of the modern world.

How then could a respected writer like Henry James make such a startling accusation? James' doubts, also shared by notable figures like Mark Twain, Sigmund Freud and Sir John Gielgud, are based on a strange mystery at the heart of one of history's most famous men.

Whilst William Shakespeare's works have inspired countless other writers, his own life is a blank sheet of paper. Most of what we know of him is in his guise as a minor businessman in the town of Stratford-upon-Avon in the English Midlands, where he was generally known as William Shakspere.

As William Shakespeare the famous writer of Elizabethan London, he is an elusive and ghostly figure, a puzzling conundrum whose biography appears wrought with contradictions and frustrating gaps. There is no record, for instance, of anybody claiming to personally know this Shakespeare during his lifetime, despite his fame and renown.

Perhaps odder still, nobody who knows Shakspere the provincial businessman from Stratford seems to have been aware that he was a famous writer. Everywhere in the biography of the author we are confronted with this dichotomy between what appears to be two very different Shakespeares.

The Stratford Shakspere, by all accounts we have, is a small and mean-spirited man. He is constantly in court over minor legal wranglings. He is a moneylender and serial tax-dodger. He hoards grain during a famine. He abandons his own young children and cruelly leaves his wife only his second-best bed in his will.

In contrast, the London Shakespeare is a man of grand ideas and imagination, a man who tackles the big universal themes with a breathtaking insight and empathy, a man with a profound and enduring appreciation for both the best and worst of the human condition. It is difficult to reconcile this great Shakespeare with the petty-minded businessman from Stratford.

Of course, many great artists are deeply flawed people; Carraviagio was a murderer and Wagner an anti-Semite, but there are reasons beyond this schizophrenic character sketch to suspect there is something very wrong with the biography of William Shakespeare.

How do we explain the records from 1597 of the London Shakespeare living in a one room hovel and being pursued for a debt of five shillings, whilst at the same time in Stratford he is a wealthy businessman who lends money and buys the town's second biggest house? Are these two different men?

Over 70 documents survive that detail the life of the Stratford Shakspere, not a single one makes any mention that he is England's greatest playwright. Indeed, Shakespeare himself never mentions he is a playwright, and neither does his family or anybody who knows them.

His will reveals nothing that might hint he was one of history's most erudite and widely read writers, no books, manuscripts or even a bookshelf. How could this wealthy man whose works were based on a huge range of sources in multiple languages own not a single book? Even stranger, Shakespeare wrote close to a million words in his own hand but not a single scrap of any of it survives.

Shakespeare's vast vocabulary and mastery of a wide range of esoteric subjects are also a difficulty for the official biography. Scholars tell us he probably attended the local grammar school from seven to thirteen. The standard curriculum would have been in latin and consisted of rote learning of the classics, arithmetic, logic, and rhetoric.

However, the Shakespeare of the plays displays an extensive knowledge of the law, philosophy, ancient and modern history, astronomy, art, music, medicine, horticulture, heraldry, even military and naval terminology and tactics. He also has an apparently insider understanding of English, French and Italian court life, the vicissitudes of Tudor-era politics and the etiquettes and pastimes of the nobility.

Shakespeare's English vocabulary is huge and he contributes hundreds of new words and phrases to our language - "All our yesterdays", "brave new world" and "in my heart of hearts" amongst them. And his skill with language was not confined to English, many of his plays are based on Greek, French and Italian sources, often untranslated into English at the time.

How could a provincial grammar school boy have gained this impressive body of knowledge without ever having attended university or even traveled abroad? Historians tell us the disconnect between the biography and the works is an inevitable consequence of Shakespeare living in an era where far less was written down, and much that was is lost. These gaps have to be filled in with intelligent, contextual guesswork, they argue.

But if we strip away these centuries of historical and culture assumptions, it does seem hard to avoid the conclusion that the two Shakespeares are not facets of the same man but, in fact, two entirely different men. Shakespeare's biography, already heavily padded out with supposition, would become fiction.

Whilst some teasing suggestions that the plays were written by someone else can be found as early as Shakespeares own lifetime, the case for alternative authors really kicked off during the Victorian era. Over 80 possible candidates have been suggested since then, ranging from Sir Francis Drake to Miguel de Cervantes and even Queen Elizebeth.

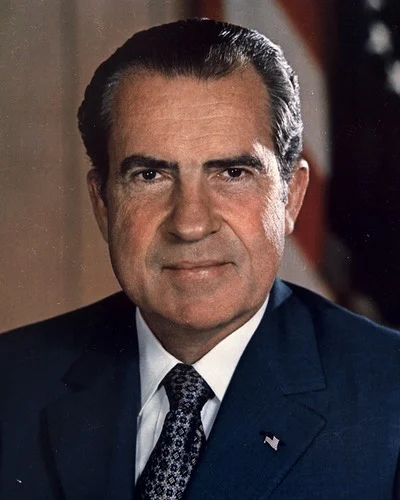

American writer Samuel Clemens knew something about pseudonyms. Famously working under the pen name Mark Twain, Clemens wrote classic works such as Huckleberry Finn, often described as the 'Great American Novel'. He came out as a Shakespeare skeptic in typically witty and satirical fashion in Is Shakespeare Dead? published in 1909.

Echoing the many mysteries of Shakespeare's life, Twain wrote - "Shall I set down the rest of the great Conjecture which constitute the Giant Biography of William Shakespeare? It would strain the Unabridged Dictionary to hold them. He is a brontosaur: nine bones and six hundred barrels of plaster."

"He is a brontosaur: nine bones and six hundred barrels of plaster"

Twain himself favored Francis Bacon as the true author, but of the many candidates suggested, the most serious study has revolved around fellow Elizabethan playwright Christopher Marlow and the aristocratic Sir Edward De Vere, the Earl of Oxford.

The anti-Stratfordians, as Shakespeare authorship skeptics are collectively known, have produced compelling cases for both men, whereas the traditional Shakespeare scholars have countered with seemingly fatal flaws in their arguments. Who is right?

Marlowe was a brilliant poet and playwright in his own right, predating Shakespeare but greatly influential upon him. His mercurial talent, along with his university education has made him many authors favored alternative candidate. However, his apparent death in a barroom fight in 1593, shortly before Shakespeare the author makes his first appearance, has led most mainstream scholars to dismiss the possibility.

Beginning in the 1920s, Essex peer Edward De Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, has emerged as the single most popular alternative candidate to be the true Shakespeare. De Vere was widely recognized as a brilliant, if volatile man, who had a classical education, possessed an intimate knowledge of the royal court and traveled extensively in France and Italy.

Critics of the Oxford theory argue that De Vere died in 1604, before some of Shakespeare's plays were supposed to be written. He also published some poems under his own name which they say are not as accomplished as the works attributed to Shakespeare.

Whilst the latter point is clearly subjective, nobody could claim De Vere was able to write plays from the grave. Did this rule the Earl out as the man behind the pseudonym? Oxfordians counter that many of Shakespeare's own plays, like Coriolanus and As You Like it, were unknown until years after his death.

Both sides do agree on one thing, writing plays could be a risky business in the late 16th century. The often bawdy theatres were exiled to the darker corners of London for fear of corrupting decent folk, and censorship for profanity and heresy were rigorously enforced by the authorities. With paranoia about the anti-reformation rife, percieved pro-catholic sentiments were often viciously suppressed. The complex world of Elizabethan royal politics also provided plenty of traps for unwary writers to fall into.

These dangers were very real. Thomas Kyd and Christopher Marlowe were tortured and persecuted for heresy, the latter possibly even murdered. Shakespeare's contemporaries like Ben Johnson and Thomas Nash were both amongst several playwrights imprisoned for writing material that displeased Queen Elizabeth.

It's plausible therefore that an aristocrat like De Vere, mindful of his political status within the Royal Court, or a bohemian free thinker like Marlowe wishing to avoid persecution, may have wanted to write their works from the safety of the shadows, using the then common Elizabethan affectation of a pseudonym.

The possibility would explain the many strange contradictions in Shakespeare's life. If the London Shakespeare was merely a mask behind which another writer hid then we could perhaps begin to add more bones to Mark Twain's metaphorical brontosaurus, and finally understand who this great writer really was.

Was 'William Shakespeare' a pseudonym for another writer?

Evidence For

A Comedy of Errors

The problems with Shakespeare's biography begin at birth, sometime in mid-April 1564, to John Shakspere, a local glovemaker and tradesman. The birth is registered in the Stratford Parish baptismal register on April 26th as William, son of John Shakspere.

Whilst it is often pointed out that spelling of names varied during Tudor times, Shakspere is what is used at young William's birth and also what is signed on his will 52 years later. In between he consistently uses Shakspere during his life in Stratford with only occasional minor variations.

It is safe, therefore to say Shakspere was what he regarded as his own name. By contrast, Shakespeare is what is used, with some minor variations, consistently during his time as a playwright in London. The most frequent variation during this time is Shake-speare, which is used exclusively in printed form and appears on close to half of his plays.

With a complete lack of documentary evidence about his early childhood, historians tell us at the age of seven the young glovemaker's son was enrolled into the local grammar school. This is the cornerstone of the Shakespeare of biography as it is during his six years at the Stratford Grammar school that Shakespeare scholars tell us the budding author must have gained the bedrock of education he needed to become the world's greatest playwright.

The problem with the scenario is there is absolutely no evidence to suggest Shakespeare ever attended the Stratford Grammar school, it's a supposition driven by circular reasoning - Shakespeare was amazingly educated so he must have attended school. But not only is there no documentary evidence (scholars say records have not survived) that Shakespeare ever received any kind of education, the reality of life for a tradesman's son dictates against it.

Shakespeare's father and family were all illiterate. John Shakspere was a glovemaker, farmer, wool dealer and tanner who also held various posts in the local community such as alderman, burgess and town bailiff. Some records indicate he occasionally indulged in usury. There is no evidence this tradesman valued education or sent any of his other children to school.

Indeed, in the hard economic times of Tudor England, would John Shakespeare have elected to send his son to a grammar school six days a week rather than train him up in one of his trades so he could contribute to the family finances?

Shakespeare is now regarded as Stratford's most famous son, and his fame throughout the world generates a great deal of tourist income for the area. However, during his lifetime, and in the years that followed his death, nobody in Stratford appeared to have the slightest idea Shakespeare was an author at all, let alone one of London's most successful and lauded.

As early as 1593, Shakespeare has become a bestselling writer; his long narrative poem Venus and Adonis was the most successful of the whole decade. Shakespeare's status and reputation continued to grow with the production of further poems and dozens of successful plays over the next twenty years.

There is not a single extant record of anybody in Stratford acknowledging this. Not Shakespeare's own family or even Shakespeare himself ever make any reference to his occupation as an author. It doesn't appear to have become a local legend of the Stratford boy made good, as is common in countless other small towns that have produced successful luminaries.

Shakespeare scholars say that his reputation as an author would have been known in Stratford, but that most people were illiterate or had no reason to write it down. If they did, the documents simply don't survive, like many records from the era.

The sounds like a reasonable explanation on the face of it. But what do we make of William Camden, one of Tudor England's most reputable historians, who wrote about Stratford and its famous men in his popular English history volume Brittania in 1607 and failed to mention Shakespeare at all?

Camden was certainly aware of the great author - in 1605, he included him in a list of who he regarded as England's finest poets. He almost certainly knew he was from Stratford too, in 1602 he had been involved in a dispute with John Shakespeare of Stratford, Shakespeare's father, over his application for a coat of arms.

None of Shakespeare's own contemporaries, like fellow Midlands poet and dramatist Michael Drayton, ever make any mention of Shakespeare in connection with Stratford. A friend of Drayton, amateur poet Thomas Greene even lived in Shakespeare's house in 1609 and mentions 'Shakspere' in his diary but never once refers to him as an author, despite Greene's own literary connections.

Dr. John Hall was a prominent Stratford physician who treated many famous and notable men during his 30 years of practice. Hall kept detailed records of his patients with the intent of publishing a casebook in his retirement. Evident in the surviving notebooks are Hall's fascination with the educational and literary achievements of the men he treats.

Hall points to works of poet Michael Drayton and dictionary compiler Francis Holyoak, but makes no mention of famous Stratford author William Shakespeare. What's so astonishing about this omission is that Hall was married to Shakespeare's own daughter Susanna and lived nearby to him for over 10 years.

Dr. Hall must surely have treated Shakespeare during his years of practice, he noted treating Susanna, so the oversight appears inexplicable. Again, for this to make sense, we must propose that Hall did in fact write about Shakespeare but that the records have simply vanished into shadows of history like so many others.

The single most important document regarding Shakespeare's life that does survive is his detailed will of 1616. This will has long puzzled scholars due to its total lack of any reference to the fact the deceased man was an author or any other clue by which we might infer he was.

Amongst Shakespeare's many belongings listed in the will, no mention is made of anything relating to his writing - no quartos of his plays, no manuscripts, no notebooks, no quills, not even any paper. Could a man who spent twenty years pouring his soul into plays not own a single copy of them? Or any other kind of art works, paintings, musical instruments, that might indicate he was a man of great culture?

Just as odd is the lack of books in Shakespeare's will. The scope of learning, knowledge of history and historical characters and familiarity with source works in multiple languages clearly demonstrated in Shakespeare's plays necessitate him owning many books. These were valuable objects at the time, yet Shakespeare makes no mention of a single volume in his will, nor even chests or bookshelves where they may have been stored.

Shakespeare scholars like to counter this inconvenient fact by saying it was not the custom at the time to leave books in your will. However, this is directly contradicted by Dr. Hall, Shakespeare's own son-in-law, who left a library of books and manuscripts in his will. Contemporary playwright Ben Jonson likewise left books in his will.

Shakespeare skeptics also point out that it wasn't until years after the Stratford Shakspere's death that anybody connected him to the author Shakespeare. The first folio of his plays printed in 1623, seven years after the Stratford man's death, makes two separate references, one to Stratford and one to Avon.

However, both these pieces of evidence are somewhat flimsy. Avon is a common place name in England and Stratford is also an area in London. No other references to the author Shakespeare in relation to Stratford upon Avon have ever been found before this, making the connection entirely posthumous.

The bust of Shakespeare at his tomb in Stratford depicting him as an author is also not contemporary to his death. It was altered long after to show him holding a quill; the original monument actually showed him with his hands on a bag of grain and gave no hint that he was a writer at all.

This Stratford Shakespeare was known to nobody as an author, had no kind of cultural life, did not own any of his own poems or plays, or any other kind of art works or books. He never attended university and evidence he ever went to school is circumstantial at best. Anything connecting the author Shakespeare to Stratford is posthumous and weak.

The only really solid facts that remain about the man from Stratford are from his business dealings, which reveal a somewhat unedifying picture of a tight-fisted, money-grubbing parochial businessman with no evident love of culture at all. He doesn't look a good fit as the author of the dazzlingly erotic Venus and Adonis, the tragic romance of Romeo and Juliet or the powerful exploration of grief and mortality of Hamlet.

The possibility then, that this seemingly piddling figure did not write the great words attributed to him is obvious. But it is not the only reason to believe the name Shakespeare may have hidden another author.

A Rose by Any Other Name

Whilst most scholars scoff at the idea that Shakespeare was a pseudonym, they do acknowledge that he was credited as the author of dozens of plays during the 17th century that he did not write. With no copyright protection, unscrupulous publishers were able to cash in on Shakespeare's reputation and erroneously attribute to him plays such as Mucedorus, The Puritan and The Merry Devil of Edmonton.

All of these plays were credited to Shakespeare after his death and probably have nothing to do with him. But other titles are more problematic. The Life of Sir John Oldcastle, A Yorkshire Tragedie and The London Prodigal were published under Shakespeare's name, but not written by him, during his own lifetime. The latter two were even staged by his own theatre company the King's Men.

With this in mind, it's hard to avoid the conclusion that the 'real' Shakespeare allowed other writers to publish works under his name on two occasions that we know of. Shakespeare was, therefore, a pseudonym at least some of the time.

According to Taylor and Mosher's Biographical History of Anonyma and Pseudonyma (1951), this is not to be unexpected - "In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Golden Age of pseudonyms, almost every writer used a pseudonym at some time or other during his career."

Not only were pseudonyms common in Elizabethan times, the use of a hyphen in the name, like Martin Mar-prelate, Cutherbert Curry-knave and Tom Tell-truth, was a particularly common form. This same verb-noun penname style, 'Shake-Speare' in this case, is used on close to half of the plays the author is credited with during his early career.

If, as Shakespeare scholars like to tell us, this is not a pseudonym, then it is one of history's most amazing coincidences, as 'Shake-Speare' just happens to make a phenomenally apt pseudonym for a writer.

The writer of the plays, whoever he was, demonstrated a thorough knowledge of ancient myth and legend, and would therefore be aware of the goddess Pallas Athena, in Greek myth born from the head of Zeus 'shaking a spear'. Most depictions of Pallas Athena, also known as Minerva, show her holding this spear.

That this spear shaking goddess was also associated with knowledge, wisdom, and the arts, could hardly be more appropriate. She was even specifically identified with playwrights by satirist Stephen Gosson in 1582, describing how the Romans would dedicate their plays to the gods, "the penning to Minerva".

These obvious parallels were not lost on contemporary authors, John Vicars described Shakespeare as he "who takes his name from the shaking and spear". Even Ben Jonson, in his introduction to the first folio in 1623, strongly makes the hint about spear shaking when he writes - "In his well torned and true filed lines, In each of which he seems to shake a lance".

"In his well torned and true filed lines, In each of which he seems to shake a lance"

Was it really a coincidence that this mysterious author, of whom we know so little, was often credited as the hyphenated Shake-Speare, a name that echoed a spear shaking goddess associated with the arts and playwrights? Could it be the real author of the plays deliberately choose the name Shakespeare as a playful allusion to he fact it was a literary pseudonym?

Some contemporary authors hinted of the deception. Joseph Hall and John Marston both refer to Shakespeare as Labeo, and poet John Davies called him 'our English Terence'. According to Suetonius, a Roman historian whose work was a popular reference source for Elizabethan authors, Labeo was a Roman nobleman who probably secretly wrote some of the work credited to the North African slave turned poet and playwright Terence.

The question is, if Shakespeare was our English Terence, who was his Labeo?

The Case for Marlowe

Before Shakespeare there was Marlowe. Although the two men were born in 1564, Marlowe's talent was far more precocious than Shakespeare's. Successful plays such as Tamburlaine (1587), The Jew of Malta (1589) and Dr. Faustus (1589), indeed all of Marlowe's known canon, predate Shakespeare's first published work, the poem Venus and Adonis in 1593.

Marlowe's work was extremely popular and influential in its time, and all mainstream scholars acknowledge his significant impact on Shakespeare. He pioneered the use of blank verse so evident in Shakespeare's plays, and the latter often borrows wholesale many of Marlowe's ideas, characters, words, and phrases. It's long been speculated early Shakespeare plays like Henry VI may even have been collaborations with Marlowe.

Marlowe proponents, or Marlovians as they are known, go much further than this and maintain their candidate was the main author of all of Shakespeare's work. Their argument centers not just on the acknowledged stylistic similarities, but the biography of Marlowe himself.

In contrast to Shakespeare, Marlowe had an excellent education, earning a masters degree at Cambridge. He was fluent in several languages and widely traveled. He was acquainted with many members of the aristocracy. He even had exotic life experiences; it is now known Marlowe was probably working periodically as a spy for the British government, operating in France, Italy and Spain.

Marlowe clearly had friends in high places, his literary patron was Sir Thomas Walsingham, courtier to Queen Elizabeth and brother of Marlowe's spymaster and head of the Secret Service Sir Francis Walsingham. He was also a member of the so-called university wits, a group of talented university educated poets and playwrights that included figures like Thomas Nash and George Peele.

In many ways, Marlowe is the best candidate to be the true Shakespeare out of all of those proposed over the years, even the Stratford man. He is the only serious alternative who was an acknowledged great writer in his own right, a man who pioneered many of the innovations Shakespeare would later use. His education, life experiences, friends and cultural life also look a perfect fit for the writer of the plays.

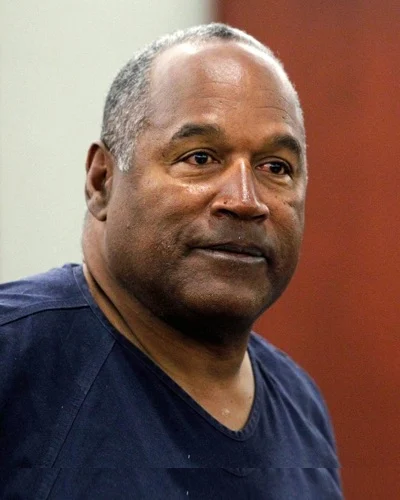

The problem, of course, is what happened in May 1593, when Marlowe's glittering career was cut tragically short by a brutal fight in a tavern in Deptford. History tells us the 29-year-old writer was killed, stabbed in the eye, after getting into a fight with three other men over a bar bill. Since this was before Shakespeare's work ever appeared in print, how could Marlowe be the true author of the plays?

This seemingly fatal flaw is an integral part of the Marlovian's theory. Marlowe was no ordinary Elizabethan author, he was a spy and had rich and powerful benefactors. They say Marlowe had gotten himself into big trouble with the authorities over heresy charges and his friends helped him evade punishment by staging his death and smuggling him out of the country to Italy.

It wouldn't be the first time Marlowe had been mysteriously protected from the consequences of his actions. In 1587, Cambridge University refused to award him his masters degree for both lack of attendance and rumors he was involved with Catholic sedition in France. The privy council, including the Queen's chief advisor Lord Burghley, intervened, ordering Cambridge to award Marlowe the degree because of his "faithful dealing" and "good service" to the Queen.

In 1592, Marlowe was arrested in Holland on serious charges of counterfeiting. When shipped back to England for prosecution, Lord Burghley again stepped in and all the charges were dropped. Incidents like these have convinced many that Marlowe was not only a spy, but an important one, for Burghley and Walsingham's Secret Service.

Had his powerful protectors again swooped in in 1593 when Marlowe faced charges of heresy? What happened in the tavern in Deptford was based on anecdote and rumor until 1923, when the previously lost coroner's report into Marlowe's death was found by American scholar J. Leslie Hotson.

All three of the men involved in the incident were in the employ of Walsingham, and the tavern in question was directly connected to Burghley. Was his apparent death actually Marlowe's last theatrical production under his own name, a ruse concocted with his fellow spies to aid his escape from the country?

From here Marlovians then contend their candidate continued to write poems and plays whilst in exile in Italy, sending them back to England under the pen name William Shakespeare. They point to the many Shakespeare plays set in Italy and the repeated theme of exile and false identity Shakespeare explores in many of his works.

The date of Marlowe's death and the appearance of Shakespeare on the literary scene is also highly suggestive. Just thirteen days after Marlowe's supposed demise in Deptford, the long narrative poem Venus and Adonis first appears under the name William Shakespeare. For Marlovians, the timing and its stylistic similarities to Marlowe's earlier poem Hero and Leander, point to this been the first work under his new nom de plume of Shakespeare.

Of course, if Marlowe really did die in the tavern in Deptford, then he is not the author of Shakespeares plays. At this point, a mercurial Earl enter's stage left.

The Case for De Vere

Edward De Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford was a theatrical soul at heart. Born in 1550 and raised in Queen Elizabeth's court, his eventful and colorful life would have made a good Shakespeare play.

Indeed, many Oxfordians believe dramatic incidents from De Vere's life are directly fictionalized in some of Shakespeare plays, a sure sign, they claim, that Oxford was their true author.

As to be expected of a man born into the aristocracy, Oxford's education was far superior to that of the Stratford Shakspere. He was tutored by some of the finest men of the age, including mathematician and occultist John Dee, studied French, Latin and law and developed a keen interest in history, philosophy, and literature.

The fact that De Vere studied law is of particular interest considering how steeped in legal terminology much of Shakespeare's writing is. Plays like Measure for Measure and the Merchant of Venice, as well as sonnets like Sonnet 46, contain complex extended legal metaphors that Oxfordians say could only come from the mind of a trained lawyer.

In terms of literary credentials to be the man behind Shakespeare's quill, Oxford does not seem to fair as well as Christopher Marlowe. Very little of the Earl's writing survives and what does are callow efforts that cannot be expected to compare to the mature writer of the plays.

However, anecdotally, at least, Oxford's had a reputation in the Royal Court as an excellent author. Francis Mere’s 1598 Palladis Tamia highly rates De Vere as a comic writer. Historian Henry Peacham, perhaps in the know, does not mention Shakespeare at all in 1622's The Compleat Gentleman, but praises Oxford as one of the leading poets of the era.

Oxford's family were also steeped in the theatre. His father had his own theatrical troupe called Oxford's Men, and Oxford himself was an important lifelong patron of the arts, including poets and writers, actors, musicians and acrobats. A group of actors sponsored by Oxford would continue to perform around the country as the Oxford Players for over twenty years.

Shakespearean actors like Mark Rylance have commented that they feel the authorial voice that comes to them through the plays is that of someone with the theatre running through their blood, and Oxford certainly fits the bill on that front.

Whilst the historical photo-fit of Oxford may resemble the author of the plays, it's De Vere's very personal connection to many of the works of Shakespeare that Oxfordians believe is their strongest suit.

When Venus and Adonis, the first credited work of Shakespeare, appeared in 1593, it was dedicated to Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton. At the time, Oxford's daughter had just become engaged to Wriothesley. Another family member, Oxford's uncle Henry Howard, actually invented the sonnet form used in Shakespeare's 156 sonnets.

Many conventional Shakespeare scholars agree that the character of Polonius in Hamlet is a quite detailed parody of Queen Elizebeth's chief counsel Lord Burghley. Burghley was Oxford's father in law and guardian when he was growing up. Oxfordians contend much of Hamlet is the deeply autobiographic work of the Earl, so closely does it resemble his real life.

If Polonius is Burghley in the analogy, then Oxford himself is Hamlet. Like Hamlet was engaged to Polonius' daughter Ophelia, Oxford was engaged to Burghley's daughter Anne Cecil. Hamlet's best friend was Horatio, Oxford's his cousin Horatio De Vere.

Both Hamlet and Oxford are courtiers, athletes, scholars, and poets; both are patrons of acting companies. Hamlet is captured at sea by pirates and left naked on the shore, something which actually happened in real life to Oxford. In the play Hamlet reads a real book called De Consolatione, Oxford was behind the first English translation of the same book.

Hamlet is often called Shakespeare's greatest play. Did its power come from the fact its real author, Edward De Vere, was writing from his own personal experiences? Oxfordians think so, and say they have found many such personal parallels to his life in Shakespeare's other plays, poems, and sonnets.

Why did De Vere simply not publish these works under his own name? The theory goes that there was a convention against the aristocracy writing plays. Political sensitivities and Oxford's desire to maintain his position in court may have also spurred him to write under the Shakespeare pseudonym.

What of Oxford's death in 1604? Ten Shakspeare plays appear after this, but Oxfordians argue this is not the same kind of problem as Marlowe's premature death is for the Marlovians. The dating of many of the plays is extremely uncertain, often fit around the chronology of the Stratford Shakspere's life. Even the official dating has several plays not appearing until the first folio, seven years after Shakespeare's death.

Perhaps there is one final clinching argument for the Oxfordians. The Earl of Oxford was a champion jouster, winning many competitions throughout Europe. After winning one bout in 1578, writer Gabriel Harvey paid tribute to Oxford in front of the Royal Court, coining his nickname by referring to him as one whose "vultus tela vibrat”, or whose "countenance shakes speares."

Evidence Against

Love's Labour's Lost

The suggestion that any author other than the Stratford Shakspere was the main writers of the plays is unequivocally rejected by all mainstream Shakespeare scholars. They cite a mass of historical, literary and contextual evidence to reject alternative candidates like Marlowe and Edward De Vere.

But perhaps the most straightforward objection is why any great writer would need to hide behind a pseudonym at all? Whoever wrote Shakspeare's plays, he dedicated 25 years of his life to writing close to a million words, some the most beautiful in the English language. All of this to hand the glory over to another?

There would need to be a compelling reason for such a profoundly painful sacrifice. Oxfordians like to argue that there was an aristocratic convention against nobleman like the Earl of Oxford writing plays under their own name, but Shakespeare scholars reject this and point to the many poems and plays Oxford apparently did write without any fear of sanction.

Marlovians say their candidate had to fake his own death and continue to write under a nom-de-plume to avoid arrest and prosecution for heresy. However since the elaborate conspiracy theory around the faked death involved some of England's most powerful men, why did they not simply have the charges of heresy dropped instead, as they had done on previous occasions Marlowe had fallen foul of the law?

As for how Marlowe could have remained undetected in exile for more than two decades, it is a matter of speculation. It was much easier to disappear in Tudor times; there were no photographs, passports or mass media. But would a colorful, hellraising character like Marlowe really not have left his mark somewhere? Or have made a deathbed confession?

Even if Marlowe, or any other secret hand behind the Shakespeare oeuvre, could keep a secret, could everyone else? With dozens of playrights and hundreds of actors operating in London during Shakespeare's time, would there not be more gossip, more rumors, more outright accusations that Shakespeare was a fake?

Methought I was enamored of an ass

Whilst much doubt surrounds the Stratford Shakspere's life and his connection to the author William Shakespeare, we can still be reasonably certain he had real, documented links to both acting and the Globe Theatre.

In 1599, Shakespeare is listed amongst other actors of the Lord Chamberlain's men, including Richard Burbage, on a lease for the Globe theatre. Court records in 1615 also show Shakespeare was a shareholder at the Globe and Blackfriars theatres.

In 1595, an entry in the accounts of the Treasurer of the Chamber reads - "William Kempe, William Shakespeare and Richard Burbage, servaunts to the Lord Chamberleyne, upon the Councille's warrant dated at Whitehall XVth Marcij 1594, for two severall comedies or enterludes shewed by them before her majestie in Christmas tyme laste".

In 1603, Shakespeare appears, along with a list of other players including Burbage, on the cast list for Ben Jonson's play Sejanus His Fall. Later that year a Royal warrant grants permission for - "William Shakespeare...and the rest of theire Assosiates freely to use and exercise the Arte and faculty of playinge Comedies Tragedies histories Enterludes moralls pastoralls Stageplaies and suche others..."

That this Shakspeare is the man from Stratford is confirmed by his own will, in which he leaves fellow Kings Company actors money to buy rings - "and to my fellows John Hemings, Richard Burbage, and Henry Condell, 26 s. 8 d. a piece to buy them rings".

It would probably be a coincidence too far to have the pseudonymous writer Shakespeare sending plays to the Globe theatre at the same time as a bit part actor was working there with almost the exact same name.

This would seem to scupper the idea that William Shakespeare was simply a pseudonym for another writer, chosen because of allusions to the spear shaking goddess Athena or the Earl of Oxford's jousting exploits.

We must therefore assume some kind of arrangement existed between the hidden hand behind the Shakespeare plays and the actor and Stratford businessman William Shakspere, whereby he would pass their work off as his own. But why would a real writer pick such an improbable person to be his cover?

If Shakspere was an uneducated provincial grain dealer as the anti-Stratfordians maintain, he would not make a very convincing candidate to act as a front man for a prolific poet and playwright. The stark contrast between Shakspere and the great works he was mysteriously producing would have been noticed.

Writing plays in the Elizabethan theatre was a far more collaborative process than it is today, and for a shifty Midlands businessman to periodically disappear down a dark alley and emerge carrying a new masterpiece, thirty-seven in all, would surely have raised more than a few eyebrows.

It would have made for a more believable ruse to choose one of the many playwrights working in the various London theatres during Shakespeare's era, someone with some kind of established literary credentials who could credibly pass the plays and poems off as his own work.

Much Ado About Nothing

A central tenet of all anti-Stratfordian thought is the conviction that the Stratford Shakspere was simply too humble in standing and education to have been able to write the lofty plays and poems attributed to Shakespeare.

However, comparison between other contemporary authors shows it is not entirely uncommon for relatively lowly figures to become accomplished and successful writers. John Webster, who wrote popular Jacobean plays The White Devil and The Duchess of Malfi, was the son of a carriage maker and like Shakespeare did not attend university.

Statistical analysis of Webster's plays, which nobody doubts were written by him, demonstrates he possesses an even larger vocabulary of words than Shakespeare or indeed any of the University wits like Christopher Marlowe, despite his lack of higher education.

Ben Jonson, Shakespeare's friend, rival and second only to him as a playwright in the Elizabethan era was the son of a bricklayer who also did not attend university. Other writers such as George Chapman and Thomas Middleton were of similarly humble stock.

For many lovers of Shakespeare, none of this really matters. The authorship question is merely a parlour game that is peripheral to the works themselves. For others, knowing who wrote the plays helps us understand them, place them in better context and perhaps even appreciate them more.

Ultimately for those who believe a glovemaker's son from Stratford wrote the greatest, most soaring works of imagination in the English language, the only important proof of authorship is the simplest one.

It is William Shakespeare's name on the front of the plays, and that is all that really counts.

Were William Shakespeare's plays written by another author under a pseudonym? - add your comment below