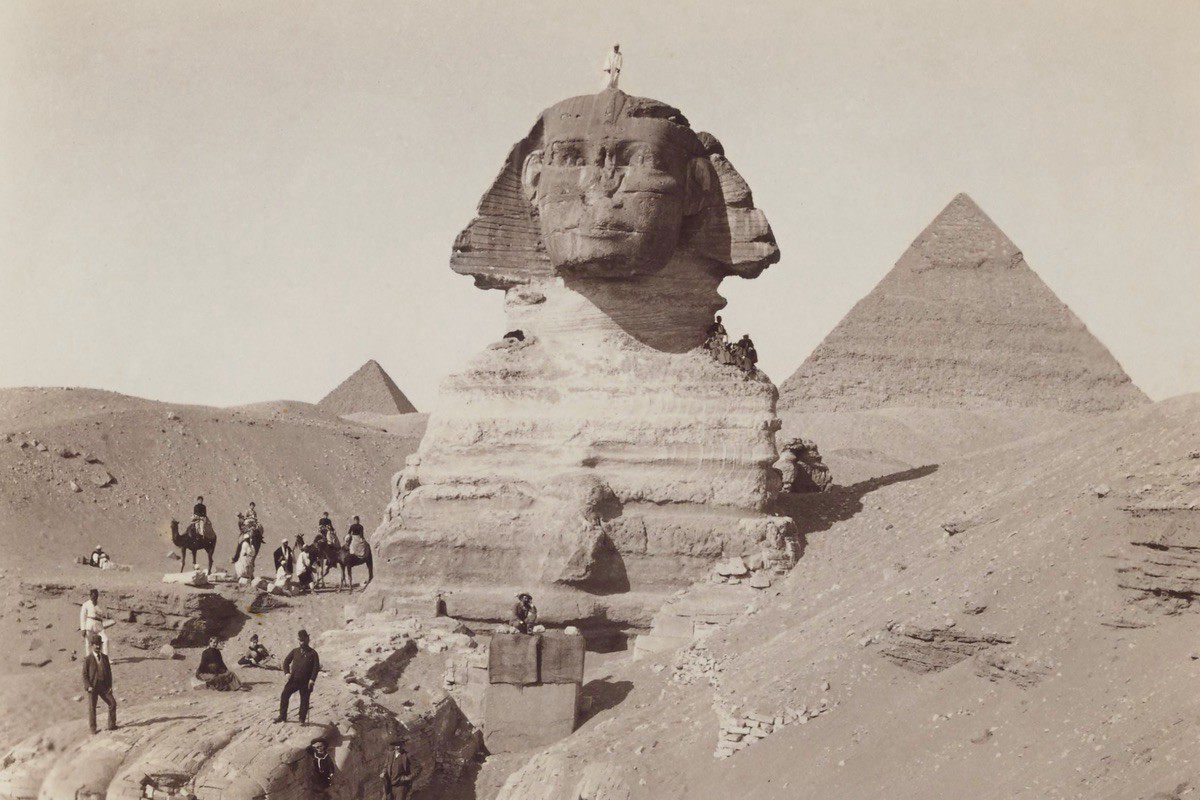

Those who stare into the inscrutable eyes of the Great Sphinx are rarely left unmoved by the experience. The vast monolithic stone monument at Giza has inspired awe and provoked mystery for millennia.

Standing near the equally mysterious pyramids of Giza, the huge sculpture depicts a mythical Sphinx, a creature with the body of a lion and the head of a man. Carved right out of the living bedrock, even today it remains the largest monolithic stone statue ever built.

Conventional wisdom tells us the Sphinx was created in the old kingdom period around 2500BC, and is a monument to the Pharaoh Khafre, the builder of the second of the three pyramids of Giza. Indeed, the face of the statue is supposed to be that of the old dynasty king.

This is, however, a fairly modern assumption. History itself is eerily silent on the enigmatic monuments true origins. There is no mention of the Sphinx in any known inscription of the old kingdom, and no other inscriptions of any date describe it’s construction.

The new kingdom pharaohs simply referred to it as Horus on the Horizon, and its modern name of Sphinx derives from the Greeks, 2000 years after its supposed construction.

Today, Egyptology's attribution of the Sphinx to Khafre is largely circumstantial. It’s location, close to the pharaoh’s pyramid, is one factor, as is a diorite statue found nearby which it is claimed bears a resemblance to the face of the Sphinx.

The only specific mention to Khafre in relationship to the Sphinx is found in the Dream Stele, erected much later by the pharaoh Thutmose in the 13th century BC. An incomplete inscription on the stele connects ‘Khaf’ to the Sphinx, but is missing the ‘re’ syllable to complete the Pharaoh’s name.

This one ambiguous partial reference, made over a thousand years later, is the best evidence Egyptology can give us for the origins of the Sphinx. The world’s most famous monumental sculpture is a mute beacon from the distant past, staring out into eternity, defying us to explain it.

But that began to change in the early 1990s when a new generation of investigators, outside of the insular world of Egyptology, began to study the Great Sphinx. What they would find would rip up the history books.

John Anthony West, an American author, and lecturer had stood in the shadow of the Sphinx many times, entranced by its strange power and beauty. For West, the mainstream consensus about its origins was unconvincing, he was sure the monument itself was telling a very different story.

Back in the 1980s, West has studied the work of French Egyptologist and occultist R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz. Inside one of his books, a dense and esoteric study of Egyptian architecture and sculpture called Sacred Science, Schwaller de Lubicz made an intriguing observation.

The Great Sphinx at Giza looked like it had been eroded by water, rather than wind and sand. Although not a geologist, West could clearly see what Schwaller de Lubicz meant. The distinctive erosion patterns looked very different to the other old dynasty monuments in the Giza complex.

How could the Sphinx, a monument surrounded by desert, even buried under sand for much of its life, have been eroded by water? West was sure the Sphinx must be much older than previously thought, so old it had stood when Egypt’s climate was far wetter that it is today, more than 7,000 years ago.

Sensing he was on the threshold of a major breakthrough, but certain that mainstream Egyptology would be hostile to his ideas, West instead turned to science. Assembling a multidisciplinary team of geologists and geophysicists, the group took to Giza in 1990 to investigate further.

Dr. Robert A Schoch, a geologist at Boston University, studied the Sphinx and its surrounding structures for several months as part of West’s team. His conclusions would cause the biggest controversy in Egyptology in its history.

According to Schoch, the deep vertical erosion patterns on the Sphinx and its enclosure could only have been caused by water. To be precise, centuries of torrential rains pouring down on the monument. Such rainfall had not occurred at Giza since at least 5,000BC, if not earlier.

The implications of this were lost on nobody. 5,000BC was not only 2 and a half millennia before Khafre had lived, it was long before any advanced civilization was known to exist anywhere in the world.

The Egyptological establishment was thrown into disarray. Dismissing the claims as ‘American hallucinations’ and calling West a charlatan, they even rubbished Schoch, a respected scientist. These initial reactions were clearly defensive and unedifying, but not unexpected.

Egyptology is not known for its tolerance to ideas from outside of its own discipline. In part, this is an inevitable consequence of the sheer number of fringe, bizarre and often outright crazy theories they have to deal with about the pyramids, that encompass everything from Atlantis to aliens.

But this was different. For the first time, hard science had intruded on their territory and it was trampling over all of its fundamental assumptions. If West and Schoch were right, the history of Egypt, and the whole ancient world would have to be rewritten.

Is the Great Sphinx of Giza really thousands of years older than previously thought?

Evidence for

Testimony in stone

In the early 1990s, geologist Robert Schoch was invited to Giza by John Anthony West to examine the weathering on the Sphinx. Although initially skeptical of the idea of an older Sphinx, Schoch soon came to concur with West’s theory.

The deep undulating vertical weathering patterns observed on the body of the Great Sphinx were, as far as Schoch was concerned, a textbook example of erosion caused by prolonged and extensive rainfall.

Schoch didn’t just study the external weathering on the body of the monument. Alongside geophysicist Dr. Thomas Dobecki, they carried out seismic studies around the statue, only to find the same distinctive rainfall induced weathering patterns in the subsurface bedrock.

Circumstantial evidence also emerged that appeared to confirm the team’s findings. Facing blocks thought to date from the Old Kingdom had been added to repair the Sphinx. Underneath, the same undulating weathering patterns were visible, indicating the repairs had been made when the Sphinx was already very ancient.

For Schoch, it was self-evident that the Sphinx had stood for millennia under heavy rainfall. Since it was widely agreed that such a climate had not existed in Egypt after about 5,000BC, either Schoch was wrong or the Sphinx was far older than the acknowledged start date for Egyptian, or any other, civilization.

In 1991, Schoch and West presented their initial findings to the American Geological Society, where they were positively received. But that would not be the case a year later when they debated representatives of mainstream Egyptology at the American Academy of Science.

By then, Schoch’s research had caused a major controversy in the world of archeology. Egyptologist Mark Lehner, acknowledged as the world’s foremost expert on the Sphinx, took particular umbrage at the idea the monument was far older than his own textbooks stated.

"I’m just following the science where it leads me, and it leads me to conclude that the Sphinx was built much earlier than previously thought"

In front of a hall full of hundreds of people, Lehner was unable to properly engage Schoch’s scientific arguments, instead demanding to know where the other evidence was for an advanced civilization that far back in antiquity.

Schoch’s response was, not unreasonably, that it this was not his problem. “I’m just following the science where it leads me, and it leads me to conclude that the Sphinx was built much earlier than previously thought”, he later said.

In 1992, Schoch and Thomas Dobecki published their findings in the peer-reviewed journals Geoarchaeology and KMT, prompting a flurry of debate amongst academia.

In response to Schoch’s evidence, some geologists offered alternative mechanisms to explain the erosion. James A. Harrell suggested the weathering was caused by moisture in the sand that had covered the Sphinx’s body for 4/5th of its existence.

However, Robert Schoch and other geologists dismissed this mechanism because it did not reflect the irregular nature of the erosion, which was concentrated in the areas most likely to be affected by rain run-off.

Schoch and West’s idea for an older Sphinx has also received some support from other geologists, although not all agree on the dates involved.

A British geologist, Colin Reader agrees with Schoch that the erosion on the Sphinx is due to rainfall but proposes a different mechanism that allows for the weathering to occur more rapidly.

Reader’s research, published in Archaeometry in 2001, was well received. But even though Reader’s conclusions are much more conservative than Schoch, he still pushes the date of the Sphinx back 500 years, which proved to be deeply unpalatable to Egyptologists.

Another geologist also backs Schoch’s basic theory but disagrees about the dating. David Coxill, writing in InScription: Journal of Ancient Egypt in 1998, contends the Sphinx must have been weathered by rainfall and pushes the dating back to before 3,000BC, although he was reluctant to go back as far as Schoch and West.

Egyptologists, however, continue to ignore the geological evidence, deciding instead to concentrate on the historical and archeological context to try and counter the case for an older Sphinx.

Where, they ask, is the evidence for an advanced civilization before 5,000BC? As Mark Lehner said when debating Robert Schoch, “If the Sphinx was built by an earlier culture, where is the evidence of that civilization? Where are the pottery shards? People during that age were hunters and gatherers. They didn’t build cities”.

Echoes of the past

Barely a decade after Mark Lehner spoke those words, his strident convictions about early civilization would be upturned in the most comprehensive way possible.

Göbekli Tepe, an extraordinary archeological site still been excavated in southeast Turkey, challenges all of our assumptions about mankind’s early history. A massive ancient temple complex, it consists of hundreds of monolithic T-shaped pillars, some weighing up to 15 tons, arranged into a series of stone circles and enclosures.

Most of the pillars contain beautiful carvings of animals, such as snakes, leopards, foxes, birds, and scorpions. These reliefs and the workmanship of the pillars attest to a high degree of sophistication and artistry from their creators, thought to be even higher than that demonstrated at Stonehenge.

Archeologists agree that Göbekli Tepe must be the product of an organized society, with teams of artisans, builders and planners required for its construction. But what’s so astonishing about it is the dating of the site, an incredible 10,000BC.

To put that into some kind of context, it’s 6000 years older than Stonehenge, a staggering 7000 years older than the mainstream dating of the Sphinx and the Great Pyramids of Giza and even thousands of years older than Robert Schoch’s controversial dating of the Sphinx.

Göbekli Tepe demonstrates that human beings were capable of monolithic masonry and sophisticated sculpture so far into the mists of prehistory that they were as further removed from the Ancient Egyptians than that great civilization is from us today.

Back in the 1990s, Egyptologists dismissed John Antony West and Robert Schoch’s theory that the Sphinx dated from before 5000BC because they couldn’t, they said, show them the pottery of such a civilization.

Göbekli Tepe goes far beyond just pottery.

Mistaken identity

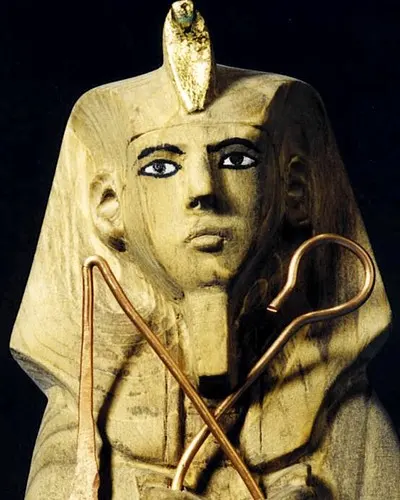

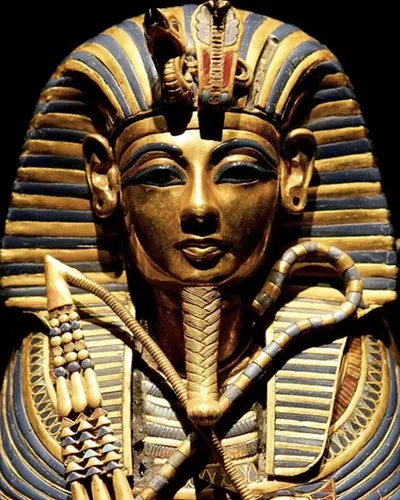

Another argument used to support the traditional, 2500BC dating of the Sphinx and its attribution to the old kingdom pharaoh Khafre, is a diorite statue of the pharaoh found close by to the Sphinx.

According to mainstream egyptology, the statue of Khafre bears a distinct resemblance to the face on the Sphinx, demonstrating that it was indeed a monument built to celebrate the pharaoh.

But does the Sphinx really look like Khafre? Clearly this was always a subjective argument, some see the similarity whilst others see no likeness at all. Again showing his flair for lateral thinking, John Anthony West decided to test the theory using forensic science.

West enlisted police artist Frank Domingo to study the face of the Sphinx. Domingo had spent 20 years creating photofits, sketching potential suspects and preparing facial reconstructions for the New York Police Department.

Domingo and his assistant traveled to Giza and took hundreds of photographs of the Sphinx and the Khafre statute that was supposed to resemble it. If the two artworks really represented the same person, Domingo was the man to find out.

Comparing the facial structure and key reference points such as eyes, noses and ears, Domingo was able to make a clear judgment. “After reviewing my various drawings, schematics, and measurements, my final conclusion concurs with my initial reaction: the two works represent two separate individuals”, Domingo stated.

“The proportions in the frontal view and especially the angles and facial protrusion in the lateral views, convinced me that the Sphinx is not Khafre. If the ancient Egyptians were skilled technicians and capable of duplicating images, then these two works cannot represent the same individual”.

If Domingo is right, then clearly the Sphinx does not depict Khafre. If it does, then the resemblance is too poor to be used as a determination of anything. Either way, the visual evidence for the conventional dating of the Sphinx is perhaps the weakest of that offered by Egyptologists.

Evidence against

Context

The main argument mainstream Egyptologists use to counter the idea of an older Sphinx is the archeological context between the statue and surrounding monuments on the Giza plateau.

Mark Lehner, the world’s leading authority on the Sphinx, contends that and the nearby Sphinx Temple and Valley Temple are related to the Sphinx, part of a larger funerary complex built by the pharaoh, Khafre.

Each monument shows a clear archeological sequence, where newer works are built incorporating older structures or constructed around them. This ‘order’ argument strongly suggests, at least to Lehner, that all of the monuments are contemporary to Khafre.

Lehner also believes the complex of monuments and temples at Giza were constructed to worship the sun god Re, offering astronomical alignments between them as further evidence.

For instance, a line drawn through the Sphinx Temple’s east-west axis passes along the right side of the Sphinx and carries on to the southside of Khafre’s pyramid. Twice a year at the equinoxes, the sun sets on this alignment, something unlikely to occur by chance and indicating a deliberate intent on the part its builders.

Geological evidence cited by Egyptologists also shows that the Sphinx, the Sphinx Temple, and the Khafre Valley Temple were all quarried from the same rock, although the sequence argument seems to indicate the Valley Temple was built first.

If that is the case, then the Sphinx is younger than the Valley temple. And if that is the case, then the argument for an older Sphinx becomes much more problematic because now several other monuments, more reliably dated to Khafre, have to be dragged into the much earlier era proposed by West and Schoch.

Ultimately this amounts to a clash of two very different sciences. At one end, we have the hard science of geology. Geology is rigorous, it can be tested by experiment, it can be shown to be false.

Archeology is a social science. It’s about interpreting the strange vagaries of human behavior, and the traces they leave behind. Whilst it is our most powerful and evocative way of understanding the past, it is also very human and very fallible.

But as this debate between science rages on, one thing remains eternal: the enigma in the sands. Aloof and defying explanation, the great monument in the deserts of Giza has always been there, as far back as mankind is able to remember.

Perhaps it always will be there. Long after we have exhausted ourselves through war or greed, the Sphinx will always be a remnant of some lost humanity, staring forever eastwards, its secrets untold.

Is the Great Sphinx of Giza thousands of years older than previously thought? - add your comment below