Leo Frank took his terrible fate with a quiet dignity. As the blind-fold was placed over his eyes he asked only that his wedding ring be given to his wife. Watched on by Atlanta's great and good, he was then hung to death from the branch of a tree.

How this mild-mannered young Jewish businessman met his brutal end is one of America's most disputed and intractable mysteries. The only uncontested fact is that a 13-year-old girl was murdered; everything else remains tainted by a shameful legacy of racism and anti-Semitism that continues to cloud the case even 100 years on.

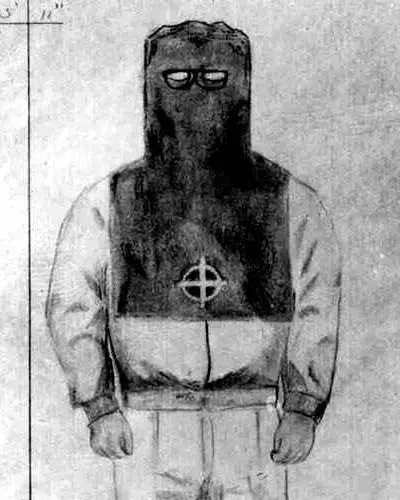

The murder of young Mary Phagan, and the subsequent arrest, conviction and lynching of Leo Frank would prove so controversial and divisive that it would prompt the formation of two organisations that could hardly be greater polar opposites - the second chapter of the KKK and the Jewish anti-defamation league.

Leo Frank's high-profile murder trial became a media circus and created deep and long-standing religious and ethnic fractures in Atlanta. For many in the Jewish community, the subsequent guilty verdict was seen as symbolic of the depth of anti-Semitism in the United States, on a par with the infamous Dreyfus affair in France.

Prominent Jewish organisations, businessmen and media tycoons rallied behind Frank's innocence and campaigned to overturn the guilty verdict. Numerous stories appeared in the press which sided with Frank and tried to cast the spotlight of blame on alternative, black, suspects.

Much of the press coverage both against and in favour of Frank was shockingly racist by today's standards, but par for the course for the American South in 1913. In a society built around discrimination, the sad murder of Mary Phagan thus became polarised between two camps of differing but equally extreme prejudices.

For those advocating Frank's innocence, he was the victim of the anti-Semitism endemic in American society; in its police and judiciary. For this camp, the true culprit was obviously the violent black man, unable to control his urge to ravage an innocent white girl.

Those who believed Frank had murdered Mary painted his supporters as part of an insidious Jewish conspiracy to help one of their own escape justice, tapping into the wider and more sinister beliefs of the time that a Jewish cabal of industrialists and bankers was taking over America.

In this feverish atmosphere, stirred relentlessly by the tabloid press, the facts of the case got lost amongst much myth and fantasy, suborned and perjured testimony and outright lies.

To try and understand the truth in this murky case, we must go back to one Saturday afternoon in 1913, when a young factory worker went to collect her wages and was never see alive again.

In early 20th century America, before child labour laws had made it illegal, it was common for girls like 13-year-old Mary Phagan to take manual work in factories. Before the safety net of social security, families like the Phagans often depended on their children working for their very survival.

Mary had worked at Atlanta's National Pencil Company factory since she was just 12-years old. Renowned in the neighbourhood for her cheerful demeanour, she was a notably pretty and popular girl who the previous Christmas had played Sleeping Beauty in the local church play.

On the afternoon of Saturday, April 26th, Mary dropped into her workplace to pick up her meagre wages for the week, hoping to then attend that day's Confederate Memorial Day parade in the town centre. She would never make it to the parade, or ever be seen alive again.

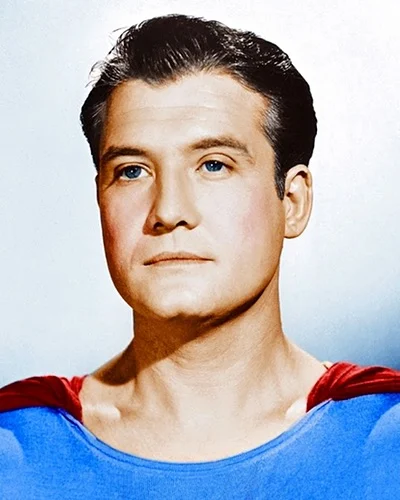

The factory's manager was Leo Frank, a 29-year-old graduate of Cornell university whose wealthy uncle owned shares in the factory's parent company. At about noon Mary made her way to his office to collect her money, an encounter Frank recalled later when interviewed by the police. He would be the last person to admit to seeing the teenager alive.

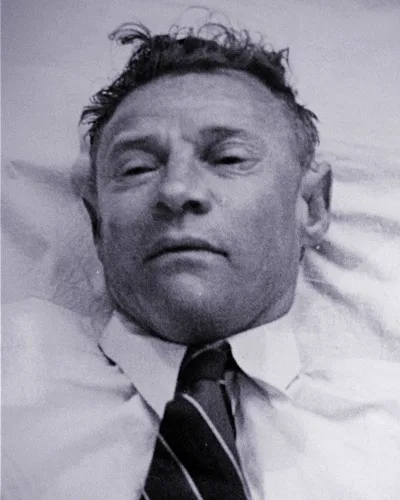

Sometime in the early hours of the next morning, the factory's night-watchman Newt Lee made a horrific discovery. In the basement of the building he found the battered and bloodied body of a young girl, so covered in dirt it was impossible to determine whether she was black or white.

It was young Mary Phagan, beaten, raped and strangled with a cord cut deep into her neck. Despite his terror that he may be blamed, as a black man, for the murder, Lee immediately fetched the local police. Lee's worry was well founded. He was arrested and charged with the crime by police, the next day a white mob gathering outside of the station with the intent of lynching him.

Whilst extra-judicial lynching had declined since its heyday in the 1890s, it was still a fairly common practice in 1913, especially against black men. Even the suspicion that Lee was involved in the rape and murder of a young white girl could have had fatal consequences for him.

Luckily, Newt Lee was saved from the mob and later cleared of any involvement. Police set about interviewing current and former workers at the factory to try and find the real culprit. Several men known to have been seen with Phagan in the past, such as a recently dismissed factory clerk John Gantt, were arrested but eventually cleared.

On Monday 1st of May detectives called around at the house of factory superintendent Leo Frank. Although not detained at this time, the officers were extremely suspicious of Frank. From the tentative timeline they had assembled of Mary Phagan's day, Frank was the last person to admit to having seen her alive.

The detectives were particularly struck by Frank's extremely nervous and agitated manner whilst talking to them. Was this strange reaction from Frank evidence of guilt or simply the reaction of a man with a noted nervous disposition not used to talking to policemen?

By now, the mood in Atlanta was one of hysteria. Thousands of people had visited the funeral home to view the dead girl's body. Demands that the murderer be found were coming from as high up as the governor and state legislature. The Atlanta Constitution newspaper even announced a then massive $1000 reward for the capture of the killer on its front page.

A coroners jury, accompanied by several Atlanta policeman, had re-examined the factory crime scene and found blond hairs and blood in the metal room near to Frank's office. Another young factory girl also testified that she had come to collect her wage shortly after Mary but Frank was not in his office. On the basis of this evidence, and his nervy demeanour, Frank was arrested on suspicion of the murder.

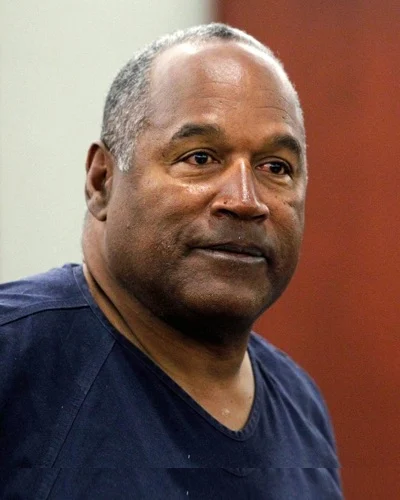

Another man, the factory's black janitor Jim Conley, was also arrested after witnesses saw him washing red stains out of a shirt in a faucet behind the factory. Whilst Conley gave numerous contradictory statements about the murder, he would later be used as the chief witness against Leo Frank at the trial.

The police now had several suspects and a lots of evidence. By far the most perplexing and confusing of this was two notes that were found near Mary's body. Ostensibly written by Mary herself, the bizarre, broken English made them virtually incomprehensible.

The first note read "he said he wood love me land down play like the night witch did it but that long tall black negro did boy his slef." The other said, "mam that negro hire down here did this i went to make water and he push me down that hole a long tall negro black that hoo it wase long sleam tall negro i write while play with me."

One thing was clear, Mary Phagan had not written these notes herself. The basement her body was found in was pitch black. It was impossible in the circumstances for a dying girl to have written the messages, and that meant only one thing. The notes had been written by her killer.

As the police developed more evidence, Leo Frank became their prime suspect. Conley was now saying that Frank had killed Phagan and he had helped him dispose of the body. Both the coroners jury and the grand jury unanimously voted to indict Frank for the murder.

The trial began on July 28th 1913, with state attorney Hugh Dorsey leading the prosecution. Dorsey attempted to portray the defendant as a sexual predator and pervert, producing a succession of young women from the pencil factory to testify that Frank had made improper advances on them.

Dorsey's ace card was Jim Conley. By now the janitors many different stories had become one damning account of how Leo Frank had murdered Mary Phagan after she rejected his sexual propositions and then ordered Conley to help him dump the body in the factory basement. The two notes, Conley told the court, were written by him but dictated by Frank.

Conley proved to be an unimpeachable witness for the prosecution, withstanding hours of defence cross-examination with a cool assuredness. Some observers felt Conley's testimony had been heavily rehearsed, almost as if he was reading from a script, but it was enough to convince the jury and Frank was unanimously convicted. On October 10th, judge Leonard S. Roan sentenced Leo Frank to hang.

Crowds of Atlantans who had been gathering outside of the courtroom over the last five weeks cheered the verdict. The sensational and salacious coverage of the trial in the newspapers had stoked up strong feelings against Frank in the city. As a Yankee jew, Atlantans were already predisposed against him and general resentment was also growing against wealthy industrialists and factory owners who were believed to be exploiting child labor to run their businesses.

The rest of America was more divided by the verdict. Whilst widely celebrated in the South, Frank's conviction was questioned in the North. Led by the New York Times, editorials appeared decrying the trial as a farce and an example of the anti-Semitism of the South. Some even suggested that Georgia was not fit for self-government.

This narrative took hold, and a campaign group of Jewish civic and business groups set out to overturn the conviction, raising $250,000 to help prove Frank's innocence. Private detectives were sent into Atlanta to review the case and numerous appeals were lodged with both the Georgian and the US Supreme Courts.

In Atlanta, Frank was still widely reviled as a child murderer and rapist, and the high-profile campaign to free him created a great deal of resentment in the area. Tom Watson, editor of the Jeffersonian tabloid newspaper, retaliated with accusations of a Northern conspiracy, headed by rich Jewish industrialists and press barons using their power to help a child murderer escape justice.

Watson's coverage flirted with ugly anti-Semitic stereotypes, but proved to be extremely popular in Georgia and served to stoke up the feeling against Frank and the Jewish community in Atlanta. It was even cited as one of the inspirations for the reformation of the KKK in the area.

Unfortunately, this increasingly hysterical mood was about to spill out from the newspapers and onto the streets in shocking fashion.

After all of his appeals failed, Leo Frank's supporters turned to state Governor John Slaton. Slaton had personally reviewed the case and come to the conclusion Frank was innocent. In the face of fierce opposition, Slatton made the fateful decision to commute Leo Frank's deaths sentence to life imprisonment.

The men that came for Leo Frank as he sat on his bunk at Milledgeville prison were remarkably solemn and organised for a mob. On the night of August 16, 1915, two dozen prominent Atlantan citizens, calling themselves the Knights of Mary Phagan, made the decision to use their Southern prerogative and dispense what they saw as the rightful verdict of the court themselves.

Armed with guns they raided the jail and drove Frank 150 miles to the site of an oak grove in Mary's hometown of Marietta, where they lynched him from a tree. The last act of the mob, none of whom were ever charged with any crime, was to return Frank's wedding ring to his wife in accordance with his last words.

The Leo Frank case had brought out the worst in everyone. Both Frank's supporters and opponents plumbed the depths in order to make their case and the wildly irresponsible newspaper coverage, with rival titles trying to one-up each other with ever more sensational stories, only served to further enrage the mood.

In recent years, there has been a growing feeling that Frank's case was a miscarriage of justice that spawned a shameful public murder. Whether prejudice played a part in his conviction is debatable, Frank was found unanimously guilty by three separate juries, some of whom were Jewish.

However, some of the evidence that they used to declare Frank's guilt looks decidedly suspect. The crucial role of the janitor Jim Conley has come under particular scrutiny - the bloody shirt, his lies to the police, his admission that he wrote the so-called murder notes, and his rehearsed testimony at the trial make Conley stand out as the likely real murderer for many advocates of Frank's innocence

The unsettling case of Leo Frank had largely been forgotten by the 1982, an unedifying episode that was best left to fade away into obscurity. That was until Alonzo Mann came forward with a bombshell - as the pencil factory's office boy in 1913, he had seen Jim Conley moving Mary Phagan's corpse by himself.

If true, it shredded a key part of the prosecution's evidence all those years ago. Did the testimony settle this most divisive of cases? Was Leo Frank innocent all along?

Evidence For

The Janitor and the Office-boy

As he approached the end of his life, 83-year-old Alonzo Mann decided to unburden himself of a dark secret that had haunted him for nearly 70 years. As Leo Frank's 14-year-old office boy in 1913, Mann had actually witnessed a co-worker trying to dispose of the body of Mary Phagan.

Mann, who testified in the original trial that he left the pencil factory at 11:30am that day and did not witness anything, was now saying he returned at about 12:05 and saw the buildings janitor Jim Conley carrying the limp body of Mary Phagan, about to throw her down the coal scuttle next to the elevator.

According to Mann's 1982 testimony, Conley threatened to kill the boy if he told anyone what he had seen. Terrified, Mann ran home and told his parents what had happened. Keen not to get involved in something so horrific, Mann says his parents ordered him to say nothing of what he had seen to the police.

Some critics have questioned Alonzo Mann's latter day statements. Is it really credible that a white family in 1913 Atlanta would be reluctant to implicate a black man in the murder of a young white girl? It's a sound criticism, but if we take Mann's about turn at face value it is clearly exculpatory for Leo Frank.

The story the prosecution told at the trial was that Conley was an accomplice after the fact, helping Frank dispose of the body in the factory's basement. Alonzo Mann says he saw Conley with Phagan's body on his own, without Frank.

Mann's 1982 story isn't the only reason to suspect Conley may have committed the murder himself. Conley was originally arrested because the pencil factory's day-watchman had seen him washing red stains out of a shirt, but it was his ever changing stories that convinced the police he had some involvement in the crime.

Conley told them he could not write, so could not be responsible for the two murder notes found near Phagan's body. Conley was quickly caught out when investigators found from co-workers that Conley could indeed write and had lied to the police.

Under extensive interrogation from detectives, the janitor then gave at least four different versions of how Frank had coerced or bribed him into helping dispose of Phagan's body and write the notes to implicate night-watchmen Newt Lee.

Whilst detectives seemed keen to believe this final version of Conley's story, it looks pretty implausible with any historical detachment. Frank was an intelligent, college educated man; a white factory owner in the racist south of 1913, would he really have hatched such a bizarre plot with a black employee, and dictated the barely literate notes found with Phagan's body?

The possibility that Conley had simply invented his story to try and deflect the blame from himself seems more believable than what he told the court during the trial. It reads like the invention of an uneducated man who had not really thought through what he was doing.

But stuck with this story, prosecutors did their best to burnish it. Conley was subjected to weeks of rehearsal, what prosecutor Hugh Dorsey called 'midnight seances'. Together with police detectives, Dorsey and his team spent hours coaching Conley, smoothing out his story to be as convincing as possible.

Conley was guided in the best way to engage jurors, to maintain eye-contact and remain composed. Conley's lawyer, William Smith, took on the role of Leo Frank's attorney, and role-played the fiercest possible cross-examination they could imagine Conley enduring, ensuring he had suitable rebuttals for anything he may be challenged on

It worked. With Leo Frank's lawyer's unable to deconstruct Conley's seemingly improbable account on the stand, his testimony did much to convict Frank in the eyes of the jury.

The Murder Notes

With the context of Alonzo Mann's 1982 admission, the idea that Conley actually committed the murder on his own, and wrote the notes to blame it on a fellow black man, looks a distinct possibility.

The references to a 'night witch' and 'negro' were widely believed to be an attempt to implicate the factory's night-watchmen Newt Lee for the crime. Lee was initially held by police after he discovered Mary's body but was later released and not thought to have been involved.

These so-called murder notes are the most bizarre aspect of the crime, and the mentality of their writer hard to fathom. They were certainly written by Jim Conley, investgators matched both the handwriting and the grammatical style to the janitor, rather than Leo Frank.

But if Leo Frank had dictated them to Conley as he claimed, its hard to understand what an intelligent, sophisticated man like Frank hoped the strange notes would achieve.

Both of the short messages, written in almost impenetrably broken English, are drafted to make them appear they were penned by Mary Phagan herself. It's extremely difficult to believe a man like Frank would ever believe anybody would buy such a ludicrous notion.

Phagan's body was found in a pitch black basement, making it impossible for her to have written them. From Frank's encounters with Mary at the factory, he would also have known she was bright and articulate, hardly someone who would write such semi-literate gibberish.

A further problem with Conley's scenario regarding the notes is he testified at the trial that Frank had ordered him to burn Phagan's body in the furnace to completely remove any trace of her from the factory. Conley claims he got drunk and never carried out this part of the plan, but if this was Frank's intention then why would he need to dictate the notes at all?

A Petty Crime

At the trial, Mary Phagan's murder was portrayed as sexually motivated. Leo Frank, the jury was told, was a pervert and deviant with a history of sexually harassing young female employees and even boys.

The prosecution found a local landlady who said Frank had attempted to rent a room for himself and a young girl on the day of the murder. Thus, a persuasive picture was painted of a man who had murdered Phagan after he attempted to initiate a sexual liaison with her and she refused his advances.

This scenario is undermined by the meagre $1.20 wages Phagan had collected from the factory that day. When police found the girls body, the money was missing. The man who had robbed her of her life and dignity had also stolen her wages.

The motive for Leo Frank to steal Phagan's money is non-existent. $1.20 would have been a pittance for the well-paid factory boss from a wealthy family. And since Frank was accused of a sexual attack, the money was not an issue anyway.

Unlike Frank, Conley did have a motive for robbing Phagan and admitted such at the trial. Conley was a drunkard and a serial debtor and even conceded under cross-examination at the trial that he would often flee his creditors by escaping from the same basement Phagan's body was found.

Had Conley, already drunk by noon when Phagan came to collect her money, tried to rob the girl? Perhaps young Mary, fiesty and strong-willed, had put up a fight and Conley had killed her in the ensuing struggle.

Whatever the specifics, this scenario seems more credible than Leo Frank stealing such a small sum from the girl himself. A further possibility is that Frank and Conley removed the money as part of their supposed attempt to frame Newt Lee, but this is dependent on how credible you regard Conley's story about the notes.

The Shit in the Shaft

Jim Conley's testimony did more than anything to seal Leo Frank's fate. Yet one strange and unpleasant admission from Frank's supposed accomplice, largely overlooked at the time, appears to seriously contradict a key aspect of his story.

Conley's startling claim was that he was in the habit of defecating in the elevator shaft, and did so earlier on the morning of Saturday the 26th, before the murder. When police first investigated the crime scene, they found the undisturbed human excrement exactly as Conley described.

The problem for the prosecution's case was that when detectives later operated the elevator, they discovered that it's crude mechanism crushed the excrement when it stopped at the basement. But Conley had told the trial that he and Frank had used this elevator to carry Phagan's corpse to the basement, something that could not have occurred without also crushing the feces.

The defence did not pursue this angle at the trial, perhaps because of its distasteful nature. It did, however, become a large part of subsequent attempts to posthumously clear Frank's name. Indeed, for some innocence advocates, the fecal matter in the elevator shaft is symbolic of the entire case against Leo Frank.

Evidence Against

A Guilty Mind

In the aftermath of the murder, numerous witnesses testified that Leo Frank was behaving in an odd manner, unusually edgy and nervous to the extent that he was unable to perform simple tasks like unlocking a door or operating the factory time clock.

The first witness to report Frank's strange demeanor was the night-watchman Newt Lee. Frank called Lee to the factory at around 4pm on Saturday afternoon, after the police believe Mary was killed but before the discovery of the body. This was unusually early according to Lee's normal routine.

Lee noted that Frank appeared on edge at this meeting. Apologizing for calling in him early, Frank told Lee that he could come back in two hours. On his return at around 6pm, Frank appeared even more nervous and agitated.

The factory boss attempted to punch a slip in the time-clock but struggled with the action that Lee had seen him perform normally on several occasions previously - "It took him twice as long this time than it did the other times I saw him fix it. He fumbled putting it in while I held the lever for him", Lee told the trial.

An ex-employee, John Milton Gantt, visited the factory at about the same time to retrieve a pair of shoes he had left there. Gantt also noticed how jumpy and nervous Frank appeared. Was Lee's odd demeanour because he had murdered Mary Phagan earlier that afternoon?

Newt Lee also recalled how Frank had phoned him later that night whilst he was carrying out his duties as a night-watchman, but before he had found the body of Mary Phagan. This was the first time Frank had ever called him like this and appeared unusual to Lee. Was Leo Frank checking to see if the body had been discovered?

After the police first contacted Leo Frank early on the morning following the murder, several officers were suspicious of just how nervous Frank appeared. Upon calling at Leo's home at around 7:00am, both Detectives Black and Rogers were taken aback by Frank's evident distress.

Black told the trial - "Frank's voice was hoarse and trembling and nervous and excited. He looked to me like he was pale. He seemed nervous in handling his collar; he could not get his tie tied, and talked very rapid in asking what had happened."

"Frank's voice was hoarse and trembling and nervous and excited..."

The officers informed Frank that Mary Phagan had been murdered in the car as they escorted him to the factory. Once there, he was shaking so badly that he had trouble unlocking doors and operating the elevator.

Frank himself would later argue at the trial that he had a naturally nervous demeanour and his behaviour was not unusual considering the circumstances. Clearly this argument can be used both ways - if Frank was the murderer than his edgy behaviour is understandable, but also equally so if he was innocent and worried that the police may wrongly suspect him.

Detectives, however, had more cause to be suspicious. Not just because of Frank's manner but his statements. On the Sunday after the murder Frank told the police that he had no idea who Mary Phagan was, an obvious lie that can only be read as a dishonest attempt by Frank to distance himself from the crime.

Phagan had worked at her current job in the factory for over a year and Frank would have encountered her on hundreds of occasions. Police found over fifty pay slips signed by Leo Frank in which he'd written Phagan's name. He also admitted he spoke to the girl at noon on the day of her murder.

Most remarkably, Frank would even try to implicate John Gantt, a former factory employee, by telling police that Gantt had been intimate with Mary in the past, signalling him out as a key suspect. Since Frank claimed not to know who Phagan was, its hard to understand how he could have known this.

Police later interviewed numerous witnesses who told them they had seen Leo Frank talking to Mary on several occasions, further betraying his lie. What some of these witnesses told detective would become a key plank of the case against him at the trial.

Wandering Hands

An alarming number of witnesses would claim that Leo Frank had a penchant for harassing young women in his employ. Some advocates of Frank's innocence have argued that this testimony was largely tittle-tattle, suborned or exaggerated statements designed to portray Frank as a pervert capable of murdering a teenage girl who spurned his advances.

However, the sheer number of people willing to say damaging things about the factory boss seems hard to countenance in the circumstances. Much has been made by Frank supporters that anti-Semitism was the reason the town turned on him, but this argument looks somewhat overstated.

In 1913 Atalanta, as with the rest of the South, Jews were a relatively well integrated and accepted part of the community. Essentially regarded as part of the white population, anti-Semitism was rare and many Jews felt the favourable atmosphere in the South made it a refuge from the discrimination they often suffered in other parts of the country.

Blacks, on the other hand, were treated as third class citizens. Stripped of many civic and legal rights, segregated, vilified and often subject to brutal violence and oppression. Most of the thousands of lynchings that occurred in this period were of black men, often killed if there was even a suspicion that they had attempted to engage in relations with white women.

In this context, it does not seem very likely that so many white Atlantans would be willing to commit perjury to see a fellow white man go to the gallows instead of any of the several black suspects that were also arrested by police.

The defense did not even attempt to cross-examine any of the teenage girls that testified at the trial that Leo Frank's had made improper advances to them. 14-year-old Nellie Pettis recounted how Frank had propositioned her for sex. 16-year-old Nellie Wood would tell the court how Frank has pushed himself against her and touched her breast. Twenty girls in all gave similar testimony about Frank's impropriety.

Several male employees also described how they had witnessed Frank rubbing himself against young female workers. Whilst not proof of guilt of the murder itself, it's not hard to see how a conservative jury of the time would be predisposed against Frank in light of such testimony.

There have been competing claims that various witnessed were got at, either bribed or coerced into false testimony by both the defense and prosecution teams. With allegations flying both ways, it's hard to know what to make of the testimony of people like Nina Formby, a rooming house owner who told the trial that Frank had telephoned her premises on the day of the murder to procure a room for himself and a young girl. Did Frank hope this girl would be Mary Phagan?

Formby would eventually recant her testimony, claiming she had made it up. However, some sources suggest Formby's boarding house was actually a child brothel, so the recantation may have been an attempt to protect her reputation. It's not an entirely outlandish allegation, the rooming house was in Atlanta's red-light district and child brothels were sadly a common feature in many Southern towns at the time.

A Problem of Time

Some of Frank's claims about his whereabouts around the time of the murder look suspect. He would tell police that he was in his office solidly from noon that day till at least 12:35. During this time, around 12:05, he says he handed over the $1.20 to Mary Phagan and saw her leave his office and talk to a girl outside.

Much of this statement did not check out when investigators attempted to corroborate it. 14-year-old Monteen Stover says she went up to Frank's office at around 12:10 that afternoon and neither Frank or Phagan were there. Stover says she did not see or talk to Phagan at all that day and the girl Frank says he saw talking to Phagan was never found despite an extensive search.

When confronted with this evidence, Frank changed his story. Now he conceded he may have "unconsciously" left his office between 12:05-12:10 to visit the metal room across the hallway from his office. This admission looked bad for Frank, as investigators had found blond hair twisted around a lathe handle in the room and blood splatter on the floor, leading them to believe this was where Phagan had actually been killed.

The metal room also housed the knurling department, where Mary Phagan worked fitting the metal bands around the rubbers on the end of the pencils. This led prosecutors to speculate that Frank had used some pretense to lure Phagan to the room in order to make a sexual advance on her.

Some forty men, across three separate juries, voted unanimously against Leo Frank back in 1915. All of his appeals were rejected. At the summation of the prosecution case, lawyer Hugh Dorsey gave a stirring pro-Jewish speech and rubbished accusations that anti-Semitism had played any part in his case at all.

Dorsey had a reputation as a moderate liberal and was not prone to demagoguery. Noted historian Albert Lindemann has written extensively on Jewish history and anti-Semitism and believes the jury convicted based on the quality of Dorsey's arguments.

"The case that Dorsey built against Frank was not based in any overt way upon anti-Semitism. Five Jews sat on the grand jury that indicted Frank. It seems safe to conclude that they were persuaded by the concrete evidence that Dorsey presented, not by his pandering to anti-Jewish feeling...", Lindemann wrote.

The case itself probably was decided by evidence, however flawed, rather than prejudice, but the poisonous war of words that surrounded the trial and its aftermath, culminating in the infamous events at the oak grove in Marietta, created a lasting legacy of resentment and paranoia which soured relations with the Jewish community in Atlanta for decades.

With overstated claims from Leo Frank's supporters and ugly anti-semitic slurs from his detractors, neither side comes out of this tragic affair well.

As for what really happened that Saturday afternoon in 1913, only two men know for sure. They are Leo Frank and Jim Conley. Credible cases can be made for both men's guilt, whereas equally viable arguments exist for their innocence.

Frank was eventually pardoned in 1986 by the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles, who did not exonerate Frank but acknowledged their failure to protect him from his lynching.

That brutal event ended any chance that Frank would ever get justice on Earth, but The Ballad of Mary Phagan, a then popular folk song inspired by the case, supposed that Frank's ultimate judgement may be faced somewhere else.

@block-ads

Was Leo Frank, imprisoned and lynched for the murder of Mary Phagan, wrongly convicted? - add your comment below